Safety 2012: Ergonomic Strategies for Managing Obesity in the Workplace

During a June 4 ASSE Safety 2012 session in Denver, Vicki Missar, CPE, associate director at Aon Risk Services, called obesity "an epidemic for the field of ergonomics."

Evolution of the Worker

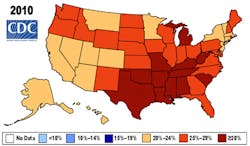

Missar told Safety 2012 attendees that 34 percent of the U.S. work force is classified as "normal weight," a figure that suggests the remaining 66 percent of American workers are not normal weight. This has implications for design guidelines, which now might apply to body types that do not reflect the majority of workers.

"The worker is changing. We're different than we were in the 1950s, 1960s. Our bodies are changing and the field of ergonomics has to look at this a little differently," Missar explained.

Increased obesity in the workplace means more arthritis, larger waist circumferences, additional work limitations, compromised grip strength, decreased lower limb mobility and medical risks. Obese employees might be more vulnerable to falls and their manual material handling ability may be compromised. Obesity also can impact self-esteem, motivation, absenteeism, presenteeism, premature mortality and more.

From an ergonomist's perspective, changing bodies means anthropometrics are outdated. Design guidelines for clothing, chairs and vehicles often are outdated and may need to shift to stay current with changing bodies.

Today's sedentary lifestyles are a big factor in obesity, Missar said. Even exercising an hour daily might not make up for an otherwise sedentary schedule. Missar advocates for at least 2.5 hours of standing every day. She recommends holding walking meetings, using standing desks and more. Holding "standing conferences" can result in more engaged and attentive employees – and it also may keep meetings short and succinct, as well.

"We've made the workplace so comfortable no one wants to get up," she said. "We've created sedentary work and sedentary bodies where we're not burning calories."

The Ergonomics-Wellness Connection

While wellness programs often promote 360-degree coverage, ergonomics typically only takes the workplace into consideration. Furthermore, most wellness programs "lack influence from an ergonomics perspective," which is a gap that must be closed, Missar said.

To approach the obesity-ergonomics issue from a holistic, wellness-based angle, Missar advocates assessing the BMI of the work force, considering the different obesity types represented in the workplace, assessing weight data and more. Ergonomists must examine how jobs are designed, communicate with engineers, develop more accurate job designs and ultimately design a plan around the growing and complex problem of an obese work force. Ergonomists also can use biomechanical models to determine what stresses occur on particular body parts during work-related activities – and how obesity can impact those stresses and limits.

Furthermore, Missar continued, ergonomists should implement early intervention screening, improve layouts and workflow, maximize 5S and create more movement in the workplace, particularly in an office setting.

"We focus so much on the individual that we've lost big picture of what we work with," Missar said. "We have to understand the obesity issue within our work force … In our field of ergonomics, we have to get on board with this and manage it better."

About the Author

Laura Walter

Laura Walter was formerly senior editor of EHS Today. She is a subject matter expert in EHS compliance and government issues and has covered a variety of topics relating to occupational safety and health. Her writing has earned awards from the American Society of Business Publication Editors (ASBPE), the Trade Association Business Publications International (TABPI) and APEX Awards for Publication Excellence. Her debut novel, Body of Stars (Dutton) was published in 2021.