Racing Successfully to the Safety Finish Line (with a Few Well-Executed Pit Stops)

Late in the afternoon of Feb. 18, 2001, race car driver Dale Earnhardt’s car crashed while turning a corner in the final lap of the NASCAR Daytona 500 in front of more than 150,000 fans and 17 million television viewers. In a flash, one of the greatest drivers in NASCAR history was gone.

Aryton Senna of Brazil, one of the greatest and most influential Formula One racers of all time, died during the 1994 San Marino Formula One Grand Prix in Imola, Italy.

These deaths shocked the motor sports world, prompting Formula One and NASCAR officials to ask themselves a critical question: “Is there any way to make our sport safer?”

The short answer is “Yes,” and they succeeded.

In the nearly two decades since Earnhardt’s fatality, not a single driver has been killed in a NASCAR cup series race. Formula One racing also went 20 years without a fatality until Jules Bianchi died after sustaining severe head injuries in the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix. There have been no Formula One fatalities since. However, there have been severe crashes, including on Nov. 29, 2020, in which Romain Grosjean’s car hit a metal barrier, split in two and burst into flames, but he escaped on his own within 30 seconds and lived.

How did NASCAR and Formula One accomplish these remarkable achievements? By establishing a learning orientation. These organizations sought to understand all the causes and contributing factors surrounding these fatal events, then applied what they learned in a systematic way to prevent or mitigate future occurrences. They now have a focus on continuous improvement in safety.

Safety professionals outside of motor sports can adopt this same successful safety learning orientation. It begins with understanding that risks come in all shapes and sizes, and prioritization is necessary. Safety professionals should follow the example NASCAR and Formula One set by adopting an obsessive focus on the prevention of those risks that could potentially lead to a serious injury or fatality (SIF).

Despite advances in safety practices, the rate of work-related accidents is not improving. Workplace fatalities are occurring at the exact same rate as 10 years ago (3.5 deaths per 100,000 workers), according to the Bureau of Labor and Statistics’ 2019 Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries. Furthermore, approximately 20-25% of recordable injuries could have easily become life-altering or fatal if only one circumstance had changed, according to Donald K. Martin and Alison A. Black’s article, “Preventing Serious Injuries and Fatalities: Study Reveals Precursors and Paradigms,” that appeared in the September 2015 issue of ASSP’s journal, Professional Safety.

But by adopting a new operating premise and three well-executed pit stops, safety professionals can address SIFs, just as NASCAR and Formula One have.

Create a culture where reporting is celebrated

Report near-misses (close calls) and use stop-work-authority, especially when SIF risk exposure is present. This is a true enabler of collecting enough meaningful data to study and make a difference in SIF prevention.

No worker should suffer consequences for stopping a job for safety reasons or reporting a near-miss with SIF potential. Rather, reinforcement and positive feedback must exist to let workers know that these behaviors of reporting risks and stopping work when SIF risk is present and not controlled are highly desirable. Yellow and red flags in professional racing are reliable and visible signals of these behaviors. A similar approach should be adopted across all industries.

Analyze safety events and data

Near-miss data, stop-work events, incident reports, operational data and real-time on-the-ground SIF precursor data related to the performance of critical controls are all vitally important sources of SIF risk vulnerability information.

All these data sources can be scrutinized for the faintest indications of SIF risk. Best-in-class approaches also determine whether there is potential for a more significant outcome to occur. When necessary, the organization should develop new and alternative means of information gathering and issue identification to better understand the risks that could lead to SIFs.

Holding risk analysis sessions with the employees who do the work and mapping out with them the way work is performed will help everyone recognize any unsafe situations that have become accepted practice. The difference between what was intended in the procedure design and what is observed in operational reality is a critical area of concern. If systems and practices are not producing data that uncovers new information on risk, they should be refreshed and rethought.

Adopt a learning orientation mindset

Insist on a learning orientation rather than a blaming orientation in the organization. Every leader and manager must buy into this concept, as it is a critical step for building what’s known as a just culture.

In the months following the Senna and Earnhardt fatalities, Formula One and NASCAR devoted concerted efforts into identifying contributory causes and looking beyond a single incident to surface additional potential issues. The broader look—and openness to modify practices—led to a deeper understanding of the safety issues drivers and pit crews faced. It wasn’t an isolated look at these individual fatalities; rather, it was a comprehensive look at the sport and the associated risks.

Deployment of lessons learned across the entire enterprise, verification of acceptance and utilization of correctional procedures are additional key operating principles for SIF prevention.

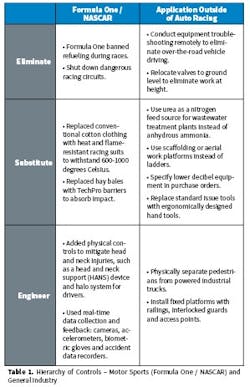

As Formula One and NASCAR have done, organizations must be diligent in constructing corrective and preventive actions that are centered in Prevention Through Design and Inherently Safer Design principles. These concepts are described in a Safety Hierarchy of Controls (HOC), whereby the top half of the HOC is significantly more reliable for controlling the development of SIF risk situations and preventing their occurrence.

The lower levels on the HOC (training, signs, use of PPE) rely heavily on human performance, and humans are far from perfect. Lower-level controls are therefore not the best long-term solution for preventing SIFs.

Serious injuries and fatalities can be prevented by controlling the precursors to these events. If an inherently risky sport such as auto racing can be made safer by building a continuous improvement mindset rooted in human safety, then every industry should be able to achieve similar results.

Rich Eagles, Don Martin and Ward Metzler are principals with DuPont Sustainable Solutions, which provides consulting services that enable organizations to protect their employees and assets, realize operational efficiencies, innovate more rapidly and build workforce capability.