Proposed Revisions to OSHA Standard Go Far Beyond Alignment with the GHS

ANALYSIS

The proposed revisions to the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (HCS) that are designed to achieve alignment with the 7th Revision to the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals (GHS) will trigger extensive compliance obligations for employers subject to the HCS. Those GHS-related changes will require: updating the label and safety data sheet (SDS) for every chemical manufactured or imported into the U.S.; updating every written program; updating every training program; providing training updates to all employees; and reclassifying many chemicals.

As extensive as those new obligations may be, they pale in comparison to the proposed new HCS requirements that have nothing to do with recent revisions to the GHS. As this article explains, OSHA has a much larger objective in mind.

Classifying a Chemical Based on Downstream Chemical Reactions with Other Chemicals

The fundamental problem with OSHA’s proposal stems from the agency’s apparent goal of dramatically expanding the scope of the hazard classification required of the chemical manufacturer or importer. In addition to classifying the product, as shipped, as well as for downstream changes in physical form, the chemical manufacturer or importer would be required to make a due diligence-based effort to:

1) identify each downstream chemical reaction of its chemical with any substance or mixture that is conducted or naturally occurs in commerce in the U.S.

2) identify each hazard posed by each of those reactions.

3) identify each product (including by-products and decomposition products) of those reactions.

4) identify and classify each hazard posed by those reaction products.

The chemical manufacturer apparently would not have to consider uses of a chemically reacted version of its product in performing the hazard classification. OSHA CPL 02-02-079, Inspection Procedures for the Hazard Communication Standard (HCS 2012), July 9, 2015 (p. 22).

The established global practice for hazard classification is to assess the inherent hazards of the chemical as shipped without considering downstream chemical reactions. This does not mean that the potential for downstream reactions is ignored. In addition to classifying for physical and health hazards, the manufacturer of a chemical is required by the HCS to provide information in Sections 5, 9 and 10 of the SDS that addresses: chemical properties (e.g., flammability, lower and upper explosion limit/flammability limit, flash point, auto-ignition temperature, decomposition temperature); stability and reactivity (e.g., hazardous reactions, conditions to avoid, static discharge, shock, vibration, incompatible materials, hazardous decomposition products, combustion products).

OSHA would achieve this unprecedented and inappropriate expansion of the HCS by amending Section 1910.1200(d)(1) and Table D.1 as follows (new language in underline, language in bold is our clarifying language):

(d)(1) Chemical manufacturers and importers shall evaluate chemicals produced in their workplaces or imported by them to classify the chemicals in accordance with this section. For each chemical, the chemical manufacturer or importer shall determine the hazard classes, and where appropriate, the category of each class that apply to the chemical being classified under normal conditions of use and foreseeable emergencies [anywhere in the chain of manufacture, distribution, and use]. The hazard classification shall include any hazards associated with a change in the chemical’s physical form or resulting from a reaction with other chemicals under normal conditions of use [anywhere in the chain of manufacture, distribution, and use]. Employers are not required to classify chemicals unless they choose not to rely on the classification performed by the chemical manufacturer or importer for the chemical to satisfy this paragraph (d)(1).

[Table D.1 Section 2] … (c) Hazards identified under normal conditions of use that result from a [downstream] chemical reaction (changing the chemical structure of the original substance or mixture)….

For those who might think (hope), despite the clear language of the revised regulatory text, that OSHA could not possibly have intended this unprecedented approach to hazard classification, the following excerpts from the Federal Register Notice should eliminate any doubt:

OSHA also proposes to add a new sentence to paragraph (d)(1) stating that the hazard classification shall include any hazards … resulting from a [downstream] reaction with other chemicals under normal conditions of use. OSHA believes this language is necessary because there has been some confusion about whether chemical reactions that occur [downstream] during normal conditions of use must be considered during classification. The agency's intent has always been to require information on SDSs that would identify all chemical hazards that workers could be exposed to under normal conditions of use and in foreseeable emergencies (see paragraph (b)(2)). This issue has been raised, for instance, when multiple chemicals are sold together with the intention that they be mixed together [downstream] before use. For example, epoxy syringes contain two individual chemicals in separate sides of the syringe that are mixed under normal conditions of use. While OSHA intends for the hazards created by the mixing of these two chemicals to be considered in classification, those hazards need only appear on the SDS … and not on the label.

OSHA notes that if it adopts the proposed revisions to [1910.1200(d)(1) and] section 2 [of the SDS template in Appendix D], hazards associated with chemicals as shipped, as well as hazards associated with a [downstream] change in the chemical’s physical form under normal conditions of use, would be presented in paragraph (a), and new hazards created by a [downstream] chemical reaction under normal conditions of use would be presented in paragraph (c)...

The final sentence of 1910.1200(d)(1) states: “Employers are not required to classify chemicals unless they choose not to rely on the classification performed by the chemical manufacturer or importer for the chemical to satisfy this paragraph (d)(1).” In practical effect, the upstream chemical manufacturer-supplier would be responsible for performing BOTH the front end of the type of chemical process hazard analysis required by the OSHA Process Safety Management Standard (29 CFR 1910.119) AND a hazard classification for each downstream chemical reaction and the reaction products of that downstream chemical reaction conducted by a downstream customer-manufacturer. Given that downstream reactions typically involve at least two chemicals, and often mixtures, that would require multiple manufacturer-suppliers to provide redundant and overlapping chemical process hazard analyses AND hazard classifications to all of these downstream user-manufacturers. This requirement would also apply upstream to the suppliers’ suppliers all the way upstream until the product supplied was a part of nature that was not processed or re-packaged, and was exempt from the HCS.

The following very simple scenario just scratches the surface on the potential impact of this proposed revision to 1910.1200(d)(1). Assume:

Manufacturer A produces and sells Chemical 1

Manufacturer B produces and sells Chemical 2

Manufacturer C purchases and combines Chemicals 1 and 2 in a chemical reaction producing Chemical 3 + By-product 1 + heat

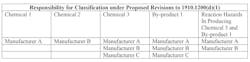

Under the proposed revision, the responsibility for hazard classifications under the proposed revisions to 1910.1200(d)(1) would be as follows:

What are the underlying policies and objectives driving this initiative? First, it seems clear that OSHA is not satisfied that the General Duty Clause, its Personal Protective Equipment Standards (including the Respiratory Protection Standard), and the current HCS provide it with the tools it would like to have to ensure downstream operators of chemical reaction processes not subject to OSHA’s Process Safety Management Standard responsibly perform their legal obligation to conduct an appropriate process hazard analysis (PHA). Second, OSHA consistently operates under a biased notion that the chemical manufacturer-supplier is generally if not always more knowledgeable about the hazards presented by the downstream reaction of its products, and the products of those reactions, than the downstream manufacturer who conducts those reactions. Finally, it appears that OSHA seeks to maintain its primary but diminished role in the area of workplace chemical safety, and implement its January 2021 Memorandum of Understanding with EPA, by requiring chemical manufacturers to develop all information that EPA could conceivably require to identify and evaluate “conditions of use” under its Procedures for Chemical Risk Evaluation Under the Amended Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), 40 CFR 702 and its new chemical review under Section 5 of TSCA). Rather than initiating a rulemaking to address these issues in an appropriate manner, it appears that the agency is attempting to subtly foist these new hazard classification requirements on the upstream supplier through this rulemaking.

To rationalize this unprecedented approach, OSHA has inappropriately conflated the scope of a manufacturer’s or importer’s hazard classification obligation under the HCS with the scope of the HCS. Section 1910.1200 provides, in relevant part, as follows:

(b)(1) This section requires chemical manufacturers or importers to classify the hazards of chemicals which they produce or import, and all employers to provide information to their employees about the hazardous chemicals to which they are exposed….

(b)(2) This section applies to any chemical which is known to be present in the workplace in such a manner that employees may be exposed under normal conditions of use or in a foreseeable emergency

(d)(1) Chemical manufacturers and importers shall evaluate chemicals produced in their

workplaces or imported by them to classify the chemicals in accordance with this section

The scope of the HCS, with respect to an individual employer’s workplace, extends to “any chemical which is known to be present in the workplace in such a manner that employees may be exposed under normal conditions of use or in a foreseeable emergency [emphasis added].” The scope of the hazard classification obligation of the chemical manufacturer or importer does not extend to every chemical known to be present in the workplace but is limited to “chemicals produced in their workplaces or imported by them.” That means the scope of a manufacturer’s hazard classification obligation under the HCS is properly limited to the hazards of the chemicals produced in its facilities, not in every downstream facility that uses its chemicals in a chemical reaction.

To support this unprecedented departure from the globally recognized principles of hazard classification and US tort law, OSHA references (in the Preamble to the Proposed Rule) three situations in which it has asserted that the HCS requires the chemical manufacturer to classify its product based on the hazards of a downstream chemical reaction. In the first example, OSHA stated (86 Fed. Reg. 9698, col. 1.):

This issue has been raised, for instance, when multiple chemicals are sold together with the intention that they be mixed together [downstream] before use. For example, epoxy syringes contain two individual chemicals in separate sides of the syringe that are mixed under normal conditions of use. … OSHA intends for the hazards created by the mixing of these two chemicals to be considered in classification ….

In that unique situation, the supplier of the syringe has designed the entire chemical reaction (selected the two reactants and designed the syringe to store the two reactants and then deliver them in the proper ratio and flow rate). The second example cited by OSHA was the chemical reaction resulting from the mixing of ready-mix cement or concrete and water. This is a unique situation in that ready-mix cement or concrete cannot perform its singular function without adding water. The only other example cited by OSHA was to unspecified by-products (such as by-products of burning fuel) and decomposition products. Again, fuel cannot perform its singular function of generating energy without combustion.

This initiative provides an excellent example of an agency inappropriately using the presence of the camel’s nose in the tent to justify bringing the camel into the tent. These three unique examples simply do not justify a proposed rule in which the manufacturer or importer (generally lacking the expertise of the manufacturer) of a chemical would be responsible for identifying: 1) every downstream chemical reaction of its chemical (with any substance or mixture) that is conducted or naturally occurs in commerce in the US; and 2) every hazard posed by any of those reactions and the products (including by-products and decomposition products) of those reactions. Such an analysis would be hopelessly complex and would be constrained by the legitimate interest and right of downstream manufacturers to protect their confidential business information from disclosure.

For many chemicals, the eventual product of such an analysis is likely to be that the chemical (after considering every reaction involving that chemical in commerce in the US) presents almost every classified hazard identified in the HCS. Because of the incredible uncertainties, and potential consequences in the toxic torts arena, no manufacturer is likely to be willing take on the risks associated with linking specific hazards to specific uses or reactions. As a result, the system would become so complex and dysfunctional as to not only be useless but to undermine the credibility of the system and OSHA, and force a gross misallocation of resources. But not to be frustrated, once the revised rule was adopted, OSHA would come to the rescue by issuing guidance requiring manufacturers to prepare their SDSs in sufficient detail to link specific hazards to specific uses or reactions.

In short, the proposal would not simply clarify the existing requirements of the HCS (with a couple hairs on the camel’s nose presently projecting into the tent)—but would require the upstream chemical supplier to perform (at least the front end of) a PHA for each downstream chemical reaction using its product and a hazard classification for each product of that reaction (akin to bringing a caravan of camels into the tent).

While OSHA’s current enforcement of the HCS may seem bearable to some, it would be highly imprudent to allow the agency to formally adopt the proposed rule and think (hope) that OSHA and the 20 plus states operating state plans would maintain the status quo in light of the likely policies and objectives discussed above. If OSHA adopts this proposed revision, how might it affect what EPA requires in connection with a new chemical submission? Finally, imagine how plaintiffs’ attorneys might use this proposed hazard classification language in the toxic tort arena to immediately shift liability to the upstream chemical manufacturer or importer from the appropriately responsible downstream employer, which is generally operating under the protection of the workers compensation shield.

With respect to the issue of classifying chemicals for the downstream hazards of chemical reactions—assuming they are listed as a separate category on the SDS and not placed on the labels, as OSHA has proposed—there appear to be three viable options:

1) Abandon the idea completely (consistent with practice in the rest of the world).

2) Limit this obligation to specifically identified chemicals and specifically identified reaction(s).

3. Retain a reworded, generic provision that clearly limits its scope to the chemical reactions explicitly recognized by the manufacturer, supported with examples.

Classifying a Chemical Based on Downstream Changes in Physical Form

The proposed revision also states that the hazard classification “shall include any hazards associated with a change in the chemical’s physical form.” If this phrase is given a reasonable interpretation, it is less objectionable than the requirement to include hazards resulting from a chemical reaction in that, while the material may change its physical form (e.g., state, particle size), it presents the same chemical composition as the shipped chemical and often involves the same hazards as those to which the manufacturer’s employees are exposed.

It would be clearly inappropriate if this “change in physical form” clause was triggered by the downstream mixing of the chemical with another chemical, which did not result in a chemical reaction. What is even more inappropriate is that the proposed “resulting from a reaction with other chemicals” clause apparently would be triggered if the chemical was first mixed with another chemical downstream and then reacted with another chemical downstream. Another concern is that there is some OSHA guidance indicating that destruction or demolition might be viewed as a “normal condition of use,” an interpretation that could significantly limit, if not eliminate the article exemption:

Exposures that may occur during the destruction of the product do not change the classification of the product as an article, as long as only a trace amount of the hazardous chemical is released. OSHA CPL 02-02-079, supra at p. 15.

That issue needs to be addressed and resolved before the “change in physical form” or “chemical reaction” clauses are adopted.

Classification of Constituents in Substances

OSHA also proposed adding the following provision to the classification scheme:

A.0.1.3 Where impurities, additives or individual constituents of a substance or mixture have been identified and are themselves classified, they should be taken into account during classification if they exceed the cut-off value/concentration limit for a given hazard class [emphasis added].

OSHA is apparently revisiting a provision that was in the original GHS and not included in HCS 2012. Obviously, it is highly unusual to place a non-mandatory recommendation in regulatory text and it seems unlikely to remain in that form. If a constituent of a substance (which may be in a mixture) is known to present an actual hazard, there is no justification for ignoring it. If constituent of a substance is known to be present but it is unclear whether it presents a health hazard, how should it be treated if its concentration exceeds the cut-off value/concentration limit for a given hazard class? Industry needs to provide an answer to that question with a well-supported rationale.

Proposed Labeling Changes (non-GHS)

On the positive side, the proposed non-GHS-related changes include several important changes to existing labeling requirements that will provide greater certainty as to what is required and will formally eliminate or modify existing requirements that have been widely recognized as infeasible and/or posing a greater hazard to employees since their adoption in 2012. The proposed small container labeling provisions would create two exemptions from the requirement to place the full label on the immediate container where it is infeasible or interferes with the intended use of the chemical.

The proposed released-for-shipment provision would eliminate the requirement to re-label containers within six months of becoming aware of new hazard information if the containers were filled and labeled, released for shipment, and were awaiting future distribution before the six months expired. For example, assume the manufacturer packages a hazardous chemical in 50 pound bags, palletizes 64 bags per pallet with an automatic palletizer, and shrink wraps each pallet. We believe OSHA recognizes that requiring the manufacturer to remove the shrink wrap, de-palletize the product, relabel the bags with an updated label and re-palletize the product is economically infeasible and creates a greater hazard to workers because of the significantly greater risk of exposure to the chemical and musculoskeletal hazards posed by those intensive manual tasks. For a situation with packaged and palletized kits, the challenge of opening and resealing or replacing outer containers would be prohibitive. Rather than maintaining a requirement to relabel containers in situations where it is infeasible and/or presents a greater hazard to workers (and therefore probably does not happen), OSHA is now acknowledging the need for an alternative approach. The proposed language should be revised to clarify that packaged and labeled product on a QA hold is product released for shipment.

The proposal would require that the manufacturer print the released-for-shipment date on the container. We anticipate that many manufacturers are not set up to do that and would find that challenging, especially if the deadline for compliance with this requirement is 60 days after the final revised rule is published in the Federal Register. OSHA should allow for the use of other mechanisms that would reliably identify the released for shipment date (e.g., lot codes). The released for shipment date obviously would not appear on product released for shipment before this change goes into effect.

A third proposal would permit the label for a bulk shipment to be placed on the immediate container, transmitted with shipping papers, or transmitted electronically as long as it is immediately available in printed form at the destination point. As proposed, it would not be a one-time label requirement as is permitted for solid metal, wood, and plastic items in Section 1910.1200(f)(4).

Compliance Deadlines

The proposal states that the final rule will go into effect 60 days after publication. It also ambiguously states:

(2) Chemical manufacturers, importers, and distributors evaluating

substances shall be in compliance with all modified provisions of this section

no later than [ONE YEAR AFTER EFFECTIVE DATE OF FINAL RULE]

(3) Chemical manufacturers, importers, and distributors evaluating mixtures shall be in compliance with all modified provisions of this section no later than 24 months after [… EFFECTIVE DATE OF FINAL RULE] [emphasis added]

The delayed compliance deadlines appear to be conditioned on the existence of an actual evaluation requirement. Is the term “evaluating” limited to “hazard classification” or does it include other tasks such as substantively revising labels or SDS to reflect revised precautionary statements? If limited to reclassification, and the manufacturer is evaluating some but not all chemicals for reclassification because of the revisions in the final rule, is the deadline extended only for the chemicals under evaluation or for all chemicals produced by the manufacturer? If a chemical manufacturer is evaluating both substances and mixtures, is the chemical manufacturer subject to the substance deadline for its substances and the mixture deadline for its mixtures?

Depending on how the compliance deadline provisions are interpreted (particularly whether the scope of the word “evaluating” is limited to hazard classification), the proposed requirement to print the released-for-shipment date on each container, and numerous other provisions (e.g., information and training, disclosure of prescribed concentration ranges for confidential concentrations and concentration ranges) could go into effect after 60 days, which would be infeasible. After the challenging HCS 2012 experience, it is incumbent on manufacturers to comment on how long it takes to implement proposed requirements.

On the other extreme, for many manufactures and importers, the tasks of performing a chemical process hazard analysis and hazard classification for downstream chemical reactions and the products of those chemical reactions would be highly burdensome if not infeasible. A manufacturer of a substance would have 14 months to complete this task. If its substance is produced in a chemical reaction by combining mixtures from two suppliers, the suppliers would apparently be responsible for performing the hazard classification—including a PHA—for the hazards of the downstream chemical reactions, but would have 26 months to complete those tasks. It is unclear how that delay would affect the last sentence in 1910.1200(d)(1), which states that the downstream “employers are not required to classify chemicals unless they choose not to rely on the classification performed by the chemical manufacturer or importer for the chemical to satisfy this paragraph (d)(1).” After the 14-month milestone, it appears that every newly discovered hazard of the substance identified by a chemical manufacturer’s ongoing investigation of downstream hazards would trigger the three and six month updating provisions of the HCS for SDS and labels, which could lead to a continuous series of reclassifications triggering those updating requirements.

Under the structure established by last sentence of 1910.1200(d)(1), a major chemical manufacturer could find itself taking on the burden and potential liabilities of a central hazard classifier for a major segment of the chemical industry. It is unclear how manufacturer-suppliers and manufacturer-users would resolve a situation in which multiple suppliers of reactants used in a particular downstream chemical reaction are required to perform a hazard classifications for that reaction and reach different conclusions, which seems likely for any chemical with broad uses.

There will be major compliance problems even if OSHA abandons the proposed requirement to address downstream chemical reactions. It is likely that chemical manufacturers of substances will take a full year to complete the required evaluation before transmitting the new SDSs and labels downstream. That means the first-tier manufacturers of mixtures will have only a year to update their hazard classifications, SDSs, and labels, and are likely to take the full year. It also means that the second-tier manufacturer of a mixture combining a mixture from a first-tier manufacturer with another mixture or substance will be out of compliance by the time it receives the required information from the first-tier manufacturer. Every newly discovered hazard of the mixture identified by an ongoing inquiry of downstream hazards would trigger the three and six month updating provisions of the HCS.

In short, the compliance deadlines are ambiguous and clearly inadequate even without the PHA requirement and the requirement to classify the hazards of the products of the downstream chemical reactions. With the addition of that requirement, it is impossible to determine what is required and when the requirement must be met because the requirements are infeasible.

Conclusion

The GHS-related portions of the proposed rule would align the classification, labeling and SDS for hazardous chemicals manufactured and imported into the US, as shipped, with Rev. 7 of the GHS and, in that way, would advance global harmonization. The proposed non-GHS-related labeling provisions would eliminate regulatory requirements that are recognized as infeasible and generally align labeling requirements with current practice. As such, they would provide greater certainty and comfort to the regulated community but would not provide any directly measurable economic benefits, much less the $27 million per year estimated by OSHA.

On the other hand, the proposed expansion of the hazard classification requirement to include the hazards of downstream chemical reactions and the products of those reactions is a recipe for either:

• chaos, a dysfunctional chemical hazard communication system, loss of credibility for OSHA and chemical hazard communication; or

• a complete restructuring of responsibilities within the chemical distribution system (generally away from where they properly reside), creation of non-tariff trade barriers, unjustified expansion of toxic tort liability, increases in insurance premiums and/or loss of coverage for toxic torts, and potentially reduced participation and competition in the US chemicals market.

The comment deadline was extended 30 days to May 19, 2021.

Lawrence P. Halprin is a partner with the legal firm Keller & Heckman LLP, based in Washington, D.C.

About the Author

Lawrence P. Halprin

Lawrence P. Halprin is a partner with the legal firm Keller & Heckman LLP, based in Washington, D.C.