Demystifying Process Safety Management for an Enabled Workforce

A rapidly aging workforce in developed economies, the lack of skilled workforces within process and extractive industries, increasingly stringent local employment requirements and an increased reliance on contractors to perform specialized tasks all are contributing factors to declining institutional knowledge among businesses.

Further complicating matters, many companies in the process and extractive industries believe employees must be engineers to understand the technologies relevant to those industries and how they operate. As a consequence, only those employees with the appropriate education or qualifications tend to be trained in advanced technologies, and some of these individuals are reluctant to share their knowledge or experience concerning specific processes and the associated risks of those processes within the organization.

These two trends largely are responsible for a scarcity of required knowledge and skills that significantly compromises the operational safety of many facilities.

While most companies understand the need to expand their training and skill development processes, the lack of a structured approach often hinders their progress. Organizations too often rely on discrete training initiatives and do not follow up with additional training to reinforce and sustain required skills. As a result, money often is spent by an organization without getting the appropriate return: a skilled workforce. Learning and development need to be a strategic imperative that is given a priority similar to a company’s other strategic business goals.

This focus on continuous learning and development particularly is critical in the area of process safety management (PSM) in order to minimize the risk of catastrophic incidents. A process safety incident potentially can have catastrophic impacts on workers, the local communities and a company’s bottom line. Implementing a structured approach to learning and development, and institutionalizing a learning and development function that focuses on professional development and building foundational knowledge and skills, are vital to successful PSM.

Why Process Safety Management Is Critical

The heart of PSM is recognizing the hazards and associated risks within an organization. Most people consider PSM to be a safety requirement rather than an operations requirement. In fact, PSM affects both the safety of the organization and its operations.

An effective PSM system allows operations to run smoothly, contributes to increased productivity and efficiency and thus extracts more value from company assets. But if PSM is not implemented with rigor and discipline, it enhances risk and hurts the productivity and efficiency of an organization.

A good illustration of this can be seen in a pressure cooker that is used in the kitchen. In order to cook, liquid and food are added to the pressure cooker, the lid is sealed and the contents start heating. As the pressurized steam builds, it cooks the contents faster. But over a period of time, the gasket in the lid starts to wear down, and when that happens, steam starts leaking. This not only contributes to increased time and energy required to cook the same amount of food, but it also increases the risk of injury.

These consequences are similar to what can happen in the workplace, but multiplied exponentially in terms of intensity and impact.

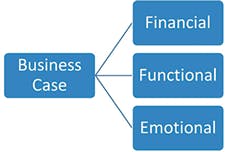

A strong business case can be made for the implementation or improvement of a PSM system. Financially, an analysis of process safety incidents can be revealing in terms of the potential cost consequences of not implementing PSM. To fully quantify risk and its potential monetary implications, both the potential direct and indirect consequences of an incident should be taken into account, not just the direct results of an event that has occurred.

From a functional perspective, a structured framework for PSM can facilitate effective decision-making on a daily basis and increase confidence among workers that they can take appropriate actions without fear of reprisal. For example, employees often are confused about their priorities due to mixed signals they sometimes receive from their line managers versus the safety manager. Workers understand the importance of continuing production, but when something goes wrong – such as an equipment malfunction – employees may feel they will be blamed for any work stoppage.

Finally, at an emotional level, many CEOs worry about the potential impact a single incident could have in terms of injuries to employees and damage to facilities – and consequently to the business itself. CEOs don’t want their legacy tied to a catastrophic incident that occurs during their tenure, so emotion is an important driver in supporting the business case for a strong PSM system.

Demystifying PSM

Many organizations already spend too much time and resources developing standards and procedures. When an incident occurs, it often results in more procedures and more documentation. Organizations tend to focus their energy on managing operations, incidents and emergencies, when in fact, it’s more important to recognize risk and the conditions in which it occur.

Recognizing potential risks requires an understanding of the hazards of materials, equipment design basics and process design basics. This risk determination provides a fundamental basis to differentiate potential risks by level of severity and by likelihood of occurrence, and then allocate resources accordingly based on these two factors. If the risk is higher, then there is an obvious need to have more layers of protection and detailed plans in place with the corresponding allocation of time, money and resources.

Of course, employees’ experiences affect how they perceive severity of risk. An employee who has worked in hazardous environments, with little or no prior repercussions, may be daring and take significant risks while working. Another person, who has experienced significant incidents and has not been exposed to hazardous environments, may be afraid to work in a particular area.

To ensure uniformity, a comprehensive process-hazards analysis (PHA) and its results should drive the design and implementation of process safety requirements. These requirements include standard operating procedure and safe work practices; mechanical integrity and quality assurance; training of personnel including contractors; incident management; changes in technology, facilities and personnel; and emergency management.

Over the years, DuPont has realized the importance of engaging workers, including operators and technicians, in PHA to create a better understanding and appreciation of risks and “why” workers are expected to perform their actions in a particular way. This gives the workforce a sense of ownership that benefits both the employee and the business.

Effectively Implementing PSM

Implementing successful PSM requires that all levels of the organization understand the consequences of following or not following prescribed PSM requirements and the impact this can have on the business in terms of injury, reputation and cost. It equally is important that employees receive the critical training, coaching and mentoring to build skills and competencies in order to avoid negative consequences.

Providing this training requires a structured process that first assesses the learning and development needs of an organization by mapping the critical functions and skills required. When developing an inventory of needed skills, the complexity of the skills, skill maturity period, availability of resources with existing PSM skills and attrition rate should be taken into account.

It is not possible, or necessary, to make every employee a PSM expert. Nor is it practical to build PSM skills and competencies overnight. But developing a PSM competency model that is customized to the organization will help address employee needs. The competency model should take into account the various roles and the levels of awareness, knowledge, skill and expertise required to implement and maintain PSM. It should be used to develop an overall roadmap for building required skills and competencies over a three-to-five-year horizon.

Once an existing skills assessment and competency model have been completed, a learning and development curriculum then can be designed based on three inputs: inventory of critical functions and skills; competency-building roadmap; and the level of competencies required for the overall organization. Importantly, the curriculum should not be viewed merely as training, but rather as an ongoing process that includes frequent reinforcement in the form of on-the-job mentoring. This approach to learning and development not only develops critical PSM skills in workers but also creates a pool of future talent knowledgeable in the organization’s safety procedures.

Finally, it is important to develop a method for evaluating the effectiveness of the learning and development program through a combination of leading and lagging metrics. For example, the number of overdue PHAs resulting from a lack of availability of competent resources could be a leading indicator.

To build the capability and improve the productivity of an organization, individual employee skills and capabilities must be developed and prioritized as a key business imperative. A structured learning and development process can motivate, engage and build important skills among employees while maintaining business and operational continuity, all of which contribute to a safer, more productive organization.

Srinivasan Ramabhadran is global practice leader for process safety and operational risk with DuPont Sustainable Solutions, based in Singapore.