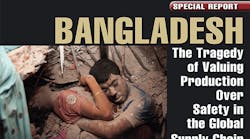

The photograph is of two workers sharing a last embrace in the collapsed Rana Plaza building, which housed factories making fashion apparel for a number of U.S. and European companies.

The photographer is Taslima Akhter, an activist/photo journalist/student now living in New York. "This photo is very special to me and our workers," she told me.

Akhter was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh, which is the site of the November 2012 Tazreen Fashions factory fire in which 112 people died. Workers at Tazreen spoke of locked emergency exits and faulty fire extinguishers. And they talked of something even more insidious and dangerous: managers who refused to acknowledge fire alarms because it meant that production would have to stop.

Mahamudul Haque, a worker in that factory, told an interviewer on PBS: "When the fire alarm was raised, our factory managers told us nothing had happened. ‘Get back to your work.' The next moment, flames of fire blew up. Everybody died, everyone. How can we deal with this?"

Then in April, the Rana Plaza building collapsed, killing over 1,100 workers and leaving hundreds more with devastating injuries. Critics were quick to point the finger at large U.S. corporations like Disney, Walmart and the Gap, which hired contractors who then hired subcontractors who operated out of facilities like Tazreen and Rana Plaza and ignored obvious hazards.

The retail industry realized it had to take a stand: "RILA members strive to ensure the safety of workers throughout their supply chains. This year, in response to the unique challenges buyers face in Bangladesh, retailers bound together to establish an industry-wide comprehensive and collaborative effort to address worker safety concerns. The collaboration, known as the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, brings coordination, considerable resources and attention to improve worker safety in Bangladeshi garment factories," said Stephanie Lester, vice president of government relations at the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA).

The alliance has developed a draft set of common safety standards and a curriculum for worker safety training and has identified ways to empower worker voices. Lester said alliance members are "committed to robust collaboration between all stakeholders, including factory owners, workers, the U.S. and Bangladeshi governments and other like-minded participants to produce lasting change in Bangladesh."

Bangladesh workers manufacture some $20 billion per year in ready-to-wear garments for U.S. and European companies. Bangladesh is the third-largest exporter of garments in the world to the United States, following only China and Vietnam. Yet Bangladesh's garment workers are among the most exploited, earning the lowest minimum wage in the world.

Multinational retailers require a high standard of quality for their garments, regardless of whether the garments are manufactured in one of their factories in the United States or one in Bangladesh. Through their demand for quality products, they've forced change. It's time they force more change by demanding safe and healthy workplaces for all workers in the global supply chain.

Here at EHS Today, we are celebrating an anniversary. Founded in 1938 as Occupational Hazards & Safety, EHS Today has covered workplace safety and health for 75 years. The same year that Occupational Hazards & Safety was launched, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which, among other things, outlawed child labor, allowed workers to organize in unions and created the 40-hour workweek.

As we went to press, hundreds of thousands of workers in Bangladesh were striking, marching in the streets and demanding the types of protections that we've taken for granted for 75 years. In Bangladesh and elsewhere, a combination of little government oversight, corrupt officials and inspectors, the demand for high-volume production, outdated or non-existent building codes, pressure from clients to increase production without raising prices and a lack of enforcement of worker protections makes it very cheap to do business, and the savings are passed on to us as consumers.

While I love a good bargain as much as the next person, I'd rather pay more for a pair of jeans than worry they were washed in blood.

I am my brother's keeper.