With our minds consumed by COVID-19 over the past few months, many people may have missed that, earlier this year, the world celebrated a grim anniversary. It was just 10 short years ago, on April 20, 2010, that an explosion rocked BP’s Deepwater Horizon Macondo oil platform operating in the Gulf of Mexico, instantly claiming the lives of 11 workers, and resulting in the largest marine environmental disaster in history.

Oddly, this milestone sparked anew my interest in the incident. One of the aspects I find most intriguing about the event is that on the morning of the disaster, senior officials at BP and Transocean, the contractor operating the rig, had arrived at the platform to celebrate a safety milestone: the site had operated for 7 consecutive years without a lost-time injury. And yet just 12 hours later, the platform, damaged and burning, toppled into the sea taking 11 lives with it.

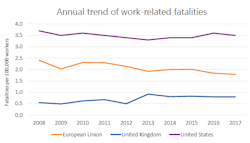

But I think the fate of Deepwater Horizon reveals a more significant truth that many organizations may have overlooked. While rates of reportable occupational incidents have been steadily declining in Western nations for nearly 20 years, the rates of serious injuries and fatalities, or SIFs, have been decreasing at a much slower rate, in some cases remaining flat or even increasing over the same period.1

How is this possible? What are we collectively getting wrong in our approach to safety management that’s producing this contradiction – that while workers are suffering fewer injuries at work, their chances of dying on the job are actually going up? And even most importantly: how many other organizations are, like Deepwater Horizon, currently celebrating “safety success” while, perhaps unknowingly, sitting on conditions rife for a catastrophic event to occur at any moment?

What hurts people isn’t the same as what kills people

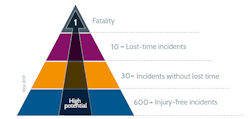

Many of the traditional strategies employed by organizations to reduce workplace injuries were derived from Herbert Heinrich’s original Safety Triangle concept. Essentially, Heinrich theorized a scale to explain the relationship between fatal and non-fatal events. The theory held that for every major injury that occurs, there are nearly 30 minor injuries and 300 non-injury events of the same nature that precede it. As a result, it was thought that by rigorously addressing the causes contributing to these lower-order events, organizations would significantly reduce the chances of those factors contributing to a fatal one.

Yet if this was the case, organizations should have seen their serious injuries and fatalities dropping at a rate comparable to that of other less-severe events. Yet they didn’t.

What later research revealed was that only a subset (roughly 20%) of these lower-order, less severe incidents had the potential to result in SIFs2. Consequently, this meant that for all the effort and resources organizations were pouring into programs to reduce minor incidents, it wasn’t having a massive impact on reducing the major ones. It’s because, as Tom Krause argues, the underlying causes or precursors for incidents with SIF potential are different compared to those without.3

Understanding SIF Precursors

In a recent whitepaper on SIF prevention4, the Campbell Institute explained that SIFs are defined as events where the following 3 factors, or precursors, exist:

1. It involves a high-risk situation or work activity

2. Critical barriers or management controls required to protect workers in these situations are absent

3. A fatality or serious injury is likely to occur if those conditions are allowed to continue.

A utility worker working in a sub-grade storm sewer would be considered engaged in a high-risk situation since the task involves a confined space entry. If that worker failed to follow proper entry protocols, such as completing atmospheric testing or lockout/tagout, and the work was permitted to continue under those conditions, then a SIF potential would exist.

Organizations then that are interested in reducing SIFs need to narrow their focus to identify the precursors within events or activities that increase SIF potential, and then analyze and reconstruct these scenarios to understand what enabled those precursors to persist. In that manner, businesses will be better able to address the underlying causes of SIFs before they can result in fatal and near-fatal outcomes.

Adjust your processes to expand your data sources

Employers looking to reduce SIFs should start by adapting their existing processes to encourage greater event reporting through a “just culture” approach. It’s widely accepted that workers who perceive they’ll be blamed for why an undesired event has occurred will be less likely to report in the first place. Yet, our ability to grow our available dataset will provide more opportunity to understand where SIF precursors exist in our business, so we can determine what to do about them. Adopting a “just culture” approach doesn’t mean that workers can’t be held accountable for actions that deviate from expectations, but it acknowledges that very often, errors are simply indicators of more ingrained system-level issues.

Beyond approaching event reporting from a “just culture” perspective, employers need to adopt tools that make it easier for workers to report events directly from their working environment, without having to track down a supervisor or fill out extensive paper forms. Mobile apps that enable workers to report incidents and observations directly from the field quickly and easily will help to ensure the company has access to the data it needs to build an accurate picture of what’s going on, and where it needs to focus its efforts.

Employers should adjust their existing event reporting process to include an assessment of SIF potential. This assessment would require workers to identify the presence of SIF precursors during event reporting and rank the overall risk that those precursors may pose to the development of SIFs.

Lastly, businesses should consider how they can leverage technology to expedite the aggregation and analysis of data to help them identify & prioritize SIF potential scenarios for further review and causal analysis. By employing business intelligence solutions we not only improve the efficiency of our data collection and analysis effort, but we’re able to link SIF metrics to EHSQ and non-EHSQ data to build structured data sets for predictive modeling that will help detect pattens and other insights to inform our SIF prevention efforts.

Enhance Your Root Cause Analysis Tools

Far too often, organizations aren’t effective at reducing SIFs because the actions they pursue do not address the underlying causes of event precursors. Instead, incidents are frequently attributed to “something the worker did” and actions are focused on correcting worker behavior only. Consequently, while the worker takes the brunt of responsibility for why the failure happened, the true causes of the event go unaddressed. While “blaming individuals may be emotionally more satisfying than targeting systems”5, it is very often less effective.

While human error often triggers an incident, these errors are in turn influenced by latent conditions – inherent flaws or weaknesses that lie dormant in our systems and processes creating error traps – circumstances or conditions that increase the probability for error. So, while a worker may have done something wrong (i.e. failed to follow a procedure), the latent condition (i.e. lack of training) likely influenced why the worker did what they did.

In order to address the underlying causes of SIFs, we need to look past the superficial errors committed by workers and dig deeper to understand the real root causes that allow these error traps and error-likely scenarios to exist. And by understanding the underlying causes of system weaknesses more thoroughly, we can design systems with greater capacity to tolerate error without resulting in critical failures that can lead to serious injuries and fatality. In this sense, we’re building greater system resilience.

Many software solutions offer organizations expansive capabilities to complete root cause analysis (RCA) using different methodologies to help reduce the risk of SIF. And vendors continue to expand their RCA tools, both through organic product development as well as integrating their platforms with best-of-breed RCA solutions to afford workers not only a credible RCA methodology, but enabling the business to then leverage the EHSQ software platform to manage associated workflows, from corrective action management to data analysis and benchmarking. These partnerships can prove invaluable to businesses looking to expand their skillsets to truly understand where SIFs are coming from and what they can do to resolve them.

Wrapping Up

SIF prevention requires organizations to rethink how they approach incident reporting, root cause analysis, and data management. Hopefully, we’ve given you some ideas to mull over, to ensure your organization isn’t the one we’re all thinking about 10 years from now.

References:

1 EU Eurostat Fatal Accidents at work by NACE, Rev 2 activity. US. BLS. Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, 2008-2017

2 Descazeaux, M. et al. 2019. Serious Injury and Fatality Prevention. Publication no. 2019-05. Institut our une culture de securite industrielle (ICSI).

3 Krause, T. and Bell, K. 2015. 7 insights into safety leadership. The Safety Leadership Institute. ISBN 13:978-0996685900.

4 Inouye, J. 2018. Serious Injury and Fatality Prevention: Perspectives and Practices. National Safety Council Campbell Institute™. Accessed at https://www.thecampbellinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/9000013466_CI_Serious-Injury-and-Fatality-Prevention_WP_FNL_single_optimized.pdf

5 Reason, J. 2000. Human Error: Models and Management. BMJ. 320(7237): 768-770.

Sean Baldry, CRSP Sean Baldry is a product marketing manager at Cority, where he is responsible for the company’s health and safety SaaS solutions. Sean has over 15 years of experience working in occupational health and safety in the construction, mining, and manufacturing industries. Prior to joining Cority, Sean was the director of health and safety for LafargeHolcim’s Eastern Canada Division. Sean is a Canadian Registered Safety Professional (CRSP).