At the 2019 Genos Annual Global Conference in Hawaii, participants from 17 different countries heard speakers around the theme of “Emotional Intelligence in the Age of Artificial Intelligence.” I was surprised to find that a session on the relationship between emotional intelligence and workplace safety made the biggest impression on me.

For years I’d heard the sayings “mind on task,” and “my emotions got the better of me,” but I hadn’t thought deeply about the correlation of these terms until Nikki Langman, learning and development specialist at cargo-handling-machinery manufacturer Cargotec, shared the impact Emotional Intelligence training has had on overall safety at her company.

Cargotec, which has a workforce of 12,000 in more than 100 countries, offers Emotional Intelligence training, through Genos, to their staff. The results Langman shared shifted my thinking on EI and its impact on safety.

For those new Emotional Intelligence, it has been defined by psychology professors Peter Salovey and John D. Mayer as “the ability to perceive emotions, to access and generate emotions to assist thought, to understand emotions and emotional meanings, and to regulate emotions reflectively to promote both better emotion and thought.” I like to simplify that to “understanding and being aware of emotions—ours and others’—in order to make better choices in negative situations and guide behavior.

Before the conference, I was aware that a lack of emotional awareness in the workplace could contribute to psychological injuries—anxiety, traumatic stress, and even depression. There are many great studies behind this. But what impacted me most about Cargotec’s results was their finding that emotional awareness can help reduce physical accidents in the workplace.

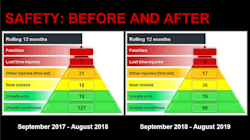

Safety – Before & After

The chart below represents the 12 months before EI training at Cargotec and the 12 months after. The results show that after training, “Lost Time Injuries” went from seven down to one. We are talking six less bodies being injured! Our greatest obligation to our employees in manufacturing is to ensure that everyone goes home safely.

The near-misses doubled from what was reported in the previous year, showing a higher level of awareness of the hazards, and the comfort to report them.

Not recognizing negative emotions, or not knowing how to react to them, can:

- Narrow our thinking

- Limit our interpretation of events

- Cause reactionary behavior

- Cause demonstration of disengagement behaviors

- Reduce performance

- Cause employees to be more easily triggered

- Have lasting effects

We want everyone on our team to be engaged and have that “mind on task,” but simply repeating that mantra will not change behavior. When we are under stress, our amygdala (a set of neurons located deep in our brain) takes over, and the subconscious brain reacts to protect us, like the fight-or-flight mode. This is great protection if we are reacting to a bear chasing us; however, that may not be helpful in a manufacturing environment. Understanding our emotions and having a self-awareness and awareness of others provides us with a foundation for making better choices and acting before our subconscious kicks in.

Should I walk all the way over to grab the grinding shield when I could quickly remove this burr right now? The safe answer—to get the shield seems logical, however, we are tempted to react quickly when we are pressured and distracted, or maybe just thinking about other things. With an awareness of our brain’s impulses—and knowledge of the long-term consequences of that burr penetrating our eyeball—we are more likely to make the right choice and get the shield.

At Cargotec, improving safety culture—through trust, communication, openness, honesty, self-management and the ability to understand different perspectives and adapt your behavior accordingly—and positively impacting the company’s safety statistics was not a projected outcome of emotional intelligence training. It is a secondary result, and bears further investigation.

Trevor Blondeel is an operations expert with more than 25 years of leadership experience in automotive manufacturing. He spent most of his career at Magna International. He now coaches manufacturing owners and leaders on how to build their skills and ultimately improve themselves and their organizations.