When lean is introduced into a safety project, most people want to end the conversation. Safety, they think, is totally different from lean. Most people still associate lean methodologies with reductions of resources and people — neither of which is good for improving workplace safety or culture.

However, the reality is that lean methodologies are holistic and all-encompassing; lean actually improves business operations to achieve operational excellence. Therefore, lean is essential to, and works in tandem, with safety.

Integrating lean methodologies with workplace safety opens up a whole new conversation about operational excellence, which now becomes operational safety excellence. To better understand this symbiotic relationship, let’s look at how lean and safety domains work together, why mindset matters and what changes help to achieve operational safety excellence.

How Lean and Safety Work Together

Lean and safety have often been perceived as separate domains within a company.

On the one hand, there are lean methodologies, of which the goal is to maximize efficiency. The lean approach is sometimes associated with ruthlessly cutting costs, sometimes by laying off employees.

On the other hand, there is safety, of which the goal is to minimize incidents that cause physical, emotional and psychological harm in the workplace, ideally bringing them to zero.

These seemingly conflicting goals raise several questions: Can safety be achieved by cutting costs? Or, is cutting costs a narrow—and incorrect—way to think about lean methodologies?

Lean comes from a quality philosophy and needs to be seen in a holistic sense, where every aspect of operations works together to increase efficiency, keep everyone safe and make the end-user happy. Lean was always meant to be a culture. But safety is considered to be a culture, too.

If the goal of lean is to improve operational excellence and continuously make things better, how can we separate it from safety? We can’t.

Safety is not an addition to lean methodologies; safety is an essential part of lean. In practice, we see that the quality department is linked to the safety department. After all, the “Q” in EHSQ represents quality.

Therefore, focusing on safety fulfills the purpose of the lean approach to manufacturing. It is past time we see these methodologies as working together to produce operational excellence.

Roadblocks to Embracing Lean

If lean methodologies and safety work hand in hand, we must first address why there is resistance or confusion when safety is mentioned. For example, if a lean expert starts talking with their client about removing operational “waste” from safety processes, the client may push back and say that safety is not about efficiency; they are unwilling to cut anything from it.

This response is likely a result of a few myths widely spread in the safety community:

- It supports the long-held belief that lean and safety are two separate domains.

- It acknowledges the fear that if safety professionals make changes to their safety procedures and something goes wrong, they will be held accountable.

- It represents an incomplete understanding of what lean is. Instead of trusting that the lean process will ultimately move toward better safety and efficiency, there is a belief that safety will be sacrificed for the sake of efficiency.

These shared beliefs represent a mindset that needs to be altered, and it must take into account people’s behaviors and cultural backgrounds. Doing so will be challenging, as it also requires utilizing clear and comprehensive communication.

Seeing ‘Waste’ in Safety Operations

In the production and maintenance domains, organizations apply lean principles to create value by reducing “waste,” as non-value-adding activities do not help to increase efficiency and do not contribute to safety for the end-user. The concept of “waste” is a carve out from Toyota lean manufacturing principles.

The same non-value-added activities are also seen widely in safety operations. These essential operations are widely excluded from lean thinking. This is a loss of opportunity, as this “waste” affects efficiency, compliance and quality.

For example, one of the well-known categories of “waste” is waiting time. As viewed from a quality perspective, waiting times have efficiency effects because people could be working instead of waiting.

But there’s also the “quality in the blinds effect.” If people are waiting for an extended period of time before they can begin a task, they tend to be rushed, causing them to be unfocused and more prone to make a mistake.

On the one hand, waiting time costs extra money and thus causes efficiency loss. On the other hand, it triggers more production risks, as workers who wait too long for the next step to be fulfilled tend to cut corners on safety.

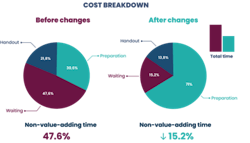

If we look closer into the structure of the total waiting time, categories of waiting time are not balanced and do not equally add value, as shown in Chart 1.

This approach to the waiting time shows how the improvement actions (i.e., flow enhancement) lead to the rebalancing of the overall time toward the activities, which can positively impact the safety of the process (i.e., more time saved for better preparation).

The lean mindset refers to seeing this “waste” in safety processes and trying to remove it for continuous improvement. But, when people who are engaged in safety processes stop looking at lean as a cost-cutting methodology and instead are taught to identify waste in their routines, they unlock new opportunities for elevating safety to a new level.

Moving from Complacency to Change

The goal for a company and its leadership team is to embrace the belief that optimizing processes will inherently enhance safety, leading to operational safety excellence. Their goal is also to encourage workers to combine lean with safety in their day-to-day routines as well as their long-term planning.

No one can impose a new mindset on someone else. Lean transformation is only possible with an empowered workforce, where each person is educated and motivated to constantly observe what needs to be improved.

Many organizations struggle with complacency, or the attitude that things will always be the same because that is how they have been. There might even be a sense of frustration or that changes are pointless.

But complacency, frustration and even boredom can be catalysts for change. When these attitudes are observed in a workforce, it is time to press in and dig deeper. Conversations need to start internally about what the pain points are. Leaders and management, along with lean experts, can start asking employees questions, such as:

- What are the pain points and areas of frustration in your role or processes?

- Why are things done this way?

- Is there anything you want to change about these processes?

This is just the starting point toward real change. The main thing is to recognize that there needs to be a mindset shift from “This is the way things are always done” to “We believe there can be positive changes.” Once a growth mindset is in place, operational safety excellence can become a joint goal.

Making the Change

However, a mindset shift is only the first step. After all, only talking or thinking about applying lean to safety doesn’t make it happen. We need to roll up our sleeves and get to work.

Companies must take action to create significant change within an organization. These steps include:

- Having a precise vision. This is literally your picture of how and what operational safety excellence looks for your company. It involves understanding what drives people on the shop floor and in the corporate office based on your company culture. Make the vision tangible, share it and—most importantly—communicate that change is possible.

- Adopting and adjusting the vision. This happens because of team interactions, specifically through open dialogue and discussions. Everyone involved must buy-in to the lean transformation; otherwise, it is unlikely to stick. Workers should perceive a vision that is not “yours” but “ours.”

- Creating a multiyear tactical plan. Make this plan agile. Make it precise in the short-term and more variable in the long term. This will allow for prioritizing initiatives around creating the most value. Instead of issuing a top-down plan, the shop floor’s voices must be heard, especially if these efforts are to be successful. Engage workers from all ranks in the planning process.

- Focusing on alignment. Once a plan is in place, gemba—the Japanese term for “actual place” that is often used to describe the shop floor or any place where value-creating work occurs—will help you refer to an aligned vision. Be present through the process. Observe, educate and support people through the transformation.

- Continuing to measure progress. Define your measurable and actionable indicators from the outset. Be sure to capture your baseline at the beginning of your journey and monitor them continuously to ensure progress. Be ready to observe deviations and take corrective actions if needed.

These are some of the broad steps for implementing true and lasting change. The lean transformation process must produce motivation and buy-in for everyone to be on the same page and empowered to make changes themselves.

Understanding People and Culture while Applying Lean to Safety

The critical caveat to change management is that every organization is unique. Neither lean nor safety have a one-size-fits-all approach because the organization’s background, structure and goals need to be considered.

Companies differ in their culture, both organizationally and by their geographical location. These cultural differences can impact processes in significant ways.

Some countries, such as the Netherlands, have a flat hierarchy structure. This means that everyone is expected to communicate their improvement ideas and opinions equally. This is different from other countries where hierarchy is significant, such as India and Vietnam. In those cultures, employees may not be comfortable speaking their opinion to management.

These cultural differences may impact lean improvement processes. They are not inherently good or bad, but it is essential to understand that they exist—and that you may need to adjust your plans accordingly. For example, in a culture with a strong hierarchical structure, a transparent system to implement new processes is best. Everyone is told precisely what to do and how to do it.

While cultural differences are significant to consider, they are just one of the many factors that contribute to an organization’s corporate culture. For lean improvement projects to make an impact, they need to be implemented with consideration of all aspects of the company’s culture, including the history, goals and size of the organization.

Conclusion

Lean and safety are not contrasting philosophies; rather, they work in tandem and belong together. What unites these frameworks is the desire to continuously raise quality and improve operational excellence. Instead of seeing lean as a cost-cutting measure, it needs to be seen as a way to make processes safer.

Lean methodologies enable the balancing of analytical information and data with people and culture. However, it is not only about cold numbers and objective facts. Lean also includes the human element of motivation and empowerment to ensure that change will occur.

Lean methodologies use both data and relationships to ultimately improve the quality of safety operations and procedures and achieve operational excellence by prioritizing both efficiency and safety.

As one of our clients, a lean expert in the global chemistry industry says, “Our excellence in operations started with excellence in safety. Lean and safety is a beautiful marriage.”

Sjoerd Nanninga is co-founder of Unite-X, a provider of safety software that helps manufacturing organizations achieve Operational Safety Excellence (OSE) and encourages continuous improvement.

About the Author

Sjoerd Nanninga

Sjoerd Nanninga is co-founder of Unite-X, a provider of safety software that helps manufacturing organizations achieve Operational Safety Excellence (OSE) and encourages continuous improvement.