ISO 45001: A Model for Managing Workplace Ergonomics

A common characteristic of organizations successful in improving workplace ergonomics is that ergonomics is managed as a process -- one that systematically identifies and effectively reduces the level of employee exposure to the risk factors known to cause musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs).

Typically, ergonomics improvement processes are based on a continuous improvement model such as the quality (ISO 9001), environmental (ISO 14001) or safety (OHSAS 18001 or ANSI Z10) models. Each of these management system models provides a common and familiar set of steps for managing environmental and safety risk, including MSD risks. The ISO 45001 Safety Management System standard provides a new, and soon to be common, model that can be used as an effective system for managing ergonomics.

MSD Risk Factors

MSD injuries continue to be a major loss in today's workplace. Fortunately, what causes MSDs is well known. The three primary risk factors are awkward posture, high force and exposure time (either long duration or high repetition).

Figure 1: Primary MSD Risk Factors

Exposure to a combination of two or all three of these risk factors increases the chance of developing discomfort, pain and/or an MSD. The threshold for each risk factor varies by body part. Large joint structures, like the shoulder and knee, have a higher tolerance for each risk factor than smaller joints. Results of epidemiologic studies have been used to develop valid, quantitative MSD risk assessment methods. In turn, these assessment methods enable safety professionals and engineers to calculate the level of risk based on the exposure to combined MSD risk factors. Applying this information to the dose-response relationship of MSD risk factors is a key measure in a continuous improvement process.

The programs and processes used to reduce MSDs vary widely among practitioners. In the 1990s, both OSHA and NIOSH promoted the implementation of an ergonomics program that included key elements and activities but did not include a specific sequence or prescribed process. The advent of total quality management (TQM) and EHS management systems launched the approach of managing safety (and ergonomics) risk as an ongoing process versus an episodic program, which leads us to management systems, specifically ISO 45001.

A New Standard

A safety management system provides a structured approach that enables an organization to control its occupational health and safety risks and improve performance. All safety management systems evolved from the quality management system (ISO 9001), which in turn was based on the Shewhart Cycle of continuous improvement (Plan-Do-Check-Act).

"To improve performance, you need to improve the system

rather than focus on the individuals"

-- W. Edwards Deming

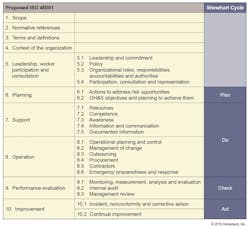

Table 1: Alignment of ISO 45001 Content with the Shewhart Cycle

ISO 45001 is an international safety management system standard. It is the product of a project committee, representing 58 countries, to establish a common, global safety management system that is consistent in steps and language with the current environmental and quality management system. The final standard was published on March 15, 2018.

ISO 45001 can also be a model on which to structure an ergonomics improvement process. This could be a standalone improvement process or an element of an organization's complete safety management system. The content of ISO 45001 aligns closely with the four steps of the Shewhart Cycle (Table 1).

So, we have the concept of a management system at a high level, but what does it look like to manage an ergonomics process as a management system?

Elements of an Ergonomics Management System

Safety management systems focus on reducing the risk of occupational injuries, illnesses and fatalities. This means that to improve workplace ergonomics, one must control the cause of MSDs.

"Manage the cause, not the results"

-- W. Edwards Deming

Using the proposed content of ISO 45001 (Table 1) as a systematic process, we present the key elements and activities in an ergonomics management system.

Leadership, Worker Participation, and Consultation

Whether managing business performance, safety or MSD reduction, an organization's performance will not improve without leadership commitment, support and sponsorship from those at the very top. Top leaders must demonstrate commitment and hold individuals accountable for their roles in the ergonomics improvement process.

Policy is a clear statement of the common direction and belief set by leadership. It establishes "true north," the common goal that aligns all people and activities involved in improvement. Establishing a risk reduction-based goal will focus your organization on systematically identifying and reducing MSD risks proactively. This is the foundation of an effective ergonomics improvement process; it keeps people on track and focused, and allows you to hold individuals accountable for their involvement and results.

Next, establish organizational roles, responsibilities, accountabilities and authorities. This means defining the distinct roles and responsibilities of people involved in the ergonomics process, and empowering them. These roles typically include a sponsor (top manager), ergonomics process lead, subject matter experts (ergonomics team members, safety committee members, ergonomists), engineers and maintenance, managers and supervisors, employees, medical staff, and safety staff. Well-defined roles and responsibilities should be used to hold individuals accountable for their involvement and results, and become the learning objective from which to design or specify training in ergonomics.

Employee participation, consultation, and representation in any process or project are critical for ensuring that workplace changes are made and improvements sustained. This is true for line employees (it is their workplace) and for engineers and maintenance personnel who are key in designing new, and modifying existing, workplaces and tools to reduce risk.

Planning

In this step, identify where action to address risk opportunities is needed. Valid quantitative MSD risk assessment tools enable subject matter experts to conduct exposure assessments and determine if exposure in a task is above or below the established threshold. They can then quickly and accurately determine the level of exposure to MSD risk factors by body part and job task; this makes it possible to combine results into a risk map across multiple workplaces.

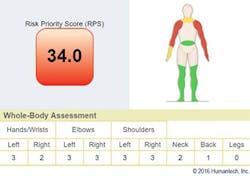

Figure 2: Example of Whole-Body MSD Risk Assessment Results

Many risk assessment tools measure exposure for a single body joint. In addition, a few whole-body assessment tools combine all exposures into a single risk score that reflects exposure for the entire body. An example is the risk priority score (RPS) in Figure 2, which combines exposures of different body parts with the total time spent performing a task. The RPS reflects the cumulative exposure in the task for use in prioritizing and selecting tasks to address.

Based on assessment findings, (Table 1) establish objectives and plans to reduce risk. Identify those tasks and workstations with exposure exceeding the threshold for MSD risk (Table 2). Combined into a risk map, this allows leaders to prioritize, select, and plan workplace changes. Plans should not be based solely on risk level, but balanced with ease of change, number of people benefitting from the improvement, product life-cycle status, trends in production volumes, productivity and quality improvements, and leveraging scheduled maintenance time and equipment change opportunities.

Support

Well-defined resources, including people, their time and funding, are necessary (Figure 3). In addition to understanding their responsibilities, individuals need to know the amount of time allotted for them to support the ergonomics process. Also determine the funding available for improvements; lack of this information has been identified as a challenge for many.

Table 2: MSD Risk Map Example Support

To ensure that people are successful in supporting the ergonomics improvement process, they must be prepared with the skills, knowledge, ability and competence to meet their defined responsibilities. Competence is achieved through training. The learning objectives of any training should be based on the responsibilities.

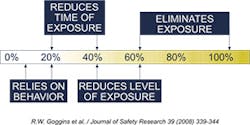

Figure 3: Cost Effectiveness of MSD Risk Factor Controls

Awareness, information and communication of an ergonomics improvement process occurs at a couple of levels and times. When preparing to launch a site process, communicate the goal, metrics to track, who is responsible for certain elements of the process and the planned timeline for implementation. After the process has been launched and established, all employees should receive regular communication of progress to the risk-reduction goals, and be made aware of specific case studies illustrating risk reduction.

- Documented information about an ergonomics improvement process should include the following, at a minimum:

- Common goal, measures and improvement plans

- Results of MSD risk assessments

- Controls implemented

- Verification of risk reduction achieved by the controls

- Engineering review of ergonomics designs in new and modified equipment, tools and layout

- Records of skills and awareness training in ergonomics

- Results of ergonomics improvement process audit

Operation

Operational planning and control means changing the workplace to reduce the level of exposure to MSD risk factors. The "ergonomics" of a workplace will not improve without changing the workplace and design of the work performed. Within the hierarchy of controls, most ergonomics improvements fall under the first and most effective type of control, engineering controls. The effectiveness of engineering controls was validated by Goggins et al. (2008) when they found that the cost effectiveness of several MSD control methods was highest when the level of exposure was eliminated or reduced through engineering changes to the workplace.

Figure 4: Example of Verification of MSD Risk Reduction

Managing change involves leveraging opportunities during equipment changes and service, and when bringing in new equipment and processes to improve ergonomics. In other words, include ergonomics in prevention through design. The cost to include ergonomics design criteria when specifying, and selecting new equipment, tools, furniture, and layout is significantly less than the cost to retrofit equipment in place. The purchasing process should be leveraged as a gatekeeper to ensure that only properly designed, low-MSD-risk equipment is introduced.

Since MSDs result from chronic exposures, the emergency preparedness and response section of ISO 45001 seems out of place. However, this portion of the ergonomics improvement process ensures that there is a system in place to manage MSD injuries when they do occur.

Performance Evaluation

Performance evaluation occurs at three levels: at individual workstations, across the organization and in response to MSD injuries.

To monitor, measure and evaluate ergonomics improvements at each workstation, conduct a follow-up MSD risk assessment using the same quantitative risk assessment method that was used for initial assessment (Figure 4). Compare the "before" risk score with the "after" risk score to verify that the exposure to MSD risk was reduced to an acceptable level, and is being maintained.

In addition to verifying the effectiveness of ergonomics improvements, follow-up assessments enable you to measure the amount of risk reduction resulting from a specific control.

The second level of performance evaluation is an internal audit of the site or company ergonomics process. A systematic review of the policy, goals, responsibilities and plans established in the planning steps identifies how well plans and goals are met. The results of the internal audit should be communicated through a management review.

Improvement

Checking for risk reduction resulting from workstation improvements and audits will generate a list of incidents, nonconformity and corrective action. Incidents refer to the investigation of suspected MSD injuries. A best practice for injury root cause analysis is to begin the investigation of MSD injuries with a quantitative risk assessment. This helps to focus the investigation on factors known to cause MSDs and helps to maintain a data-driven, repeatable process. Include the same valid MSD risk assessment tools used during Planning.

Every management system includes an element to ensure that non-conformity is addressed and corrective actions are taken and completed. Non-conformance may indicate equipment and tools not designed to established design criteria, risk exposure at a task exceeds the acceptable level, improvement goals and metrics are not being met, or a site ergonomics process is falling short of company standards. In each case, tracking non-conformance, ensuring action and holding individuals accountable for corrective action are essential for success.

Continual Improvement

This is the final step to sustain the ergonomics improvement process over time -- through staffing and management changes, expense controls and market fluctuations -- and to learn from and adjust the process to fit future needs, resources and priorities.

Putting it into Practice

Best practices for sustaining the ergonomics improvement process described in this article include the following:

Ensure that adequate controls and actions are in place (and supported by top management) to reduce MSD risk factors to the lowest level achievable.

Apply effective risk-reduction controls at other similar tasks and workstations.

Provide necessary resources to continually find and reduce MSD risks.

Regularly review and track the status of the ergonomics process and plans within the normal business tracking process.

Involve all levels of the organization in identifying and addressing MSD risks in daily operations.

And finally, manage MSD risks and ergonomics as a process that follows a common or familiar set of steps. ISO 45001 uses terminology and structure, like quality and environmental management systems, to enable you to do just that within your organization and across your enterprise.

Walt Rostykus, CSP, CPE, CIH, FAIHA is a principal consultant, and Rick Barker, CPE is a senior consultant with Humantech Inc., a provider of workplace improvement and ergonomics solutions.

References

Deming, W.E. (1982). Out of the Crisis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Center for Advanced Educational Services, Cambridge, Mass.

Goggins, R., Spielholz, P., & Nothstein, G. (2008). Estimating the effectiveness of ergonomics interventions through case studies: implications for predictive cost-benefit analysis. Journal of Safety Research, 39(3), 339-344.

Humantech, Inc. (2014). Summary of Benchmarking Study Results: Cost and Return on Investment of Ergonomics Programs. Retrieved March 3, 2018, from https://www.humantech.com/resources/whitepapers/

International Organization for Standardization (ISO). (2015). Draft International Standard ISO/DIS 45001. Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems– Requirements with Guidance for Use.

Humantech, Inc. (2011). Summary of Benchmarking Study Results: Elements of Effective Ergonomics Program Management. Retrieved March 3, 2018, from https://www.humantech.com/resources/whitepapers/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (1997). Musculoskeletal Disorders and Workplace Factors, A Critical Review of Epidemiologic Evidence for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Neck, Upper Extremity, and Low Back. Cincinnati: NIOSH.

About the Author

Walt Rostykus

principal consultant

Walt Rostykus, CSP, CPE, CIH, FAIHA is a principal consultant with Humantech Inc., a provider of workplace improvement and ergonomics solutions.

Rick Barker

senior consultant

Rick Barker, CPE is a senior technical ergonomics manager with VelocityEHS | Humantech, a provider of cloud-based environment, health, safety (EHS) and sustainability solutions.