Sudden cardiac arrest is the leading cause of death in the United States, striking approximately 380,000 Americans each year. This is despite the fact that prompt treatment with an automated external defibrillator, or AED, can save victims' lives.

How are employers obligated to manage the risk of someone going into sudden cardiac arrest in the workplace? To determine the best answer to this question, safety managers must consider the expectations and legal recourses available to workers, customers, vendors and any others who might suffer sudden cardiac arrest on company property.

Following the law is just one aspect of meeting this duty. Yes, a safety manager must make sure that the organization complies with regulations pertaining to AED programs. But meeting statutory requirements does not always fulfill a company's risk management responsibilities for sudden cardiac arrest. Businesses should take additional precautions to minimize potential legal consequences while demonstrating a commitment to the health and safety of workers, customers and others on the premises.

‘Common-Law Duty'

An interesting case in the California Supreme Court shows the potential legal ramifications of being without an AED. Verdugo v. Target Corp. asks the question: "In what circumstances, if ever, does the common-law duty of a commercial property owner to provide emergency first aid to invitees require the availability of an AED for cases of sudden cardiac arrest?" The question stems from a lawsuit filed by the mother and brother of a woman who died from sudden cardiac arrest while shopping in Target's Pico Rivera store near Los Angeles. The case is expected to be decided later this year.

The legal challenge to Target comes despite California having no statutory requirement for an AED to be available on commercial property, explains Richard Lazar, an AED program expert and founder of Readiness Systems LLC, which helps organizations create and maintain AED programs. Even so, the retail giant is not the first organization to be put to the test of "common-law duty."

Under common law, judges and juries use the concepts of "community expectations" and "reasonableness" to determine the "standard of care" in a particular circumstance, Lazar explains. Safety managers must understand these concepts and consider the impact that they might have if sudden cardiac arrest occurs.

Court decisions hinge on what judges and juries define as being reasonable and expected by a community, Lazar notes. Their decisions define the standard of care that must be met. It's the job of a safety manager to anticipate what a jury might consider to be a reasonable precaution for sudden cardiac arrest, and to make decisions about AEDs according to that judgment.

In other words, simply complying with the law might not be enough.

Would workers and customers expect an AED to be available? Employers must apply common-sense practicality to their thinking about AED programs. They must consider whether an AED would be expected. If the answer is "yes," would the AED be operationally ready at a moment's notice? For example, failing to save a customer – either due to having no AED or to having a unit with a dead battery – could spur a common-law challenge. Failing to save a co-worker for one of the same reasons could lead to a larger-than-usual workers' compensation settlement while having a detrimental impact on employee morale and public relations.

Some organizations only look at statutory requirements and base their decisions about AED programs on those considerations alone, Lazar says. It's important for safety managers to look at a bigger picture and consider common law, workers' compensation laws, industry norms, worker and customer expectations, organizational values and more, he adds.

For example, mandates in some states for AEDs in schools, fitness centers and dental offices – coupled with AEDs becoming more commonplace in workplaces and public areas – might create a reasonable expectation for an AED to be located in every workplace. In addition, AEDs are more commonplace in some industries than in others, sometimes as a result of a legal challenge. Airlines, health clubs, transportation authorities, theme parks and other organizations have paid settlements or damages for failing to have AEDs or for not having staff properly trained to use them. In many cases, damages were paid in the absence of statutes requiring AEDs.

Upside to Having an AED

Safety managers also should consider the upside to having an AED. A workplace with an AED on the premises simply has a better chance of saving a sudden cardiac arrest victim than it would by depending on EMS. That's because even the fastest EMS team likely will need several minutes to travel to the rescue site, and quickly providing a defibrillating shock is the most important aspect of AED lifesaving. Up to 90 percent of sudden cardiac arrest victims receiving AED treatment within two minutes survive, but the survival chances decrease with each passing minute. By 10 minutes, most victims die.

A Johns Hopkins study of sudden cardiac arrest responders concluded that "speed is more important than training." Non-medical volunteers – including employees in workplaces – coming to the rescue with AEDs achieved the highest survival rate (40 percent), which was higher than health care workers (16 percent) and police (13 percent). Non-medical volunteers achieved the higher rate simply because they arrived on the scene sooner, the study determined.

"On average, early AED defibrillation before EMS arrival seems to nearly double a victim's odds of survival after [out-of-hospital cardiac arrest]," the study's authors wrote.

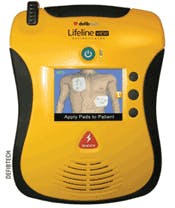

Technological innovations occurring within the past several years have made AEDs easy to use. The life saves made by non-medical users – including bystanders who have not received AED/CPR training – prove this ease of use. These improvements include real-time video and text instructions for rescuers, built-in self-training modules and maintenance reminders. A survey by Defibtech and Harris Interactive found that an AED with video, audio and text instruction would be used with confidence by up to 95 percent of the respondents.

Today's AEDs are like smartphones – easy to use and intuitive. But no matter how many state-of-the-art features an organization's AEDs have, safety managers still must make sure that batteries and defibrillation pads are checked and replaced periodically. For large organizations with many AEDs located on their properties, this ongoing maintenance can be a challenge. Most AED providers can recommend outsourced services that can help with this upkeep.

Managing risk, therefore, requires many considerations, from understanding the legal environment to using common-sense strategies for maintaining AEDs. By looking at this big picture, safety managers can put their organizations in the best place to succeed for financial stakeholders, employees and customers.

Debra Ford is director of marketing for Guilford, Conn.-based Defibtech, which designs and manufactures Lifeline and ReviveR and related accessories. Contact her at [email protected].