Workplace injuries are on the rise—another dire result of COVID-19. During VelocityEHS’ virtual event, The Short Conference, nearly 500 attendees were polled on worker stress and muscular discomfort experienced since the onset of COVID-19. Eighty-nine percent reported that their essential workers were experiencing the same to significantly more stress and muscular discomfort. When asked if they expected workplace musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) to decrease or increase once all employees return to work, 95% felt they would either stay the same or increase.

Deconditioning of the Industrial Athlete

It makes sense that office workers are at a higher risk—many were immediately told to work from home when the pandemic began and not given adequate equipment. The best way to explain the higher injury risks for the industrial worker is to consider the career of an athlete.

When an athlete takes a hiatus, either due to an injury or after a competitive event, endurance levels and strength capabilities begin to diminish. We’ve all heard the phrase “use it or lose it”—well, it’s true. According to many exercise professionals and fitness app blogs, if we start to slack (or stop training all together), deconditioning begins and is noticeable within as few as seven days, and after a prolonged break (a month or two), we can experience a significant or almost complete loss of fitness. The actual timeframes depend on the individual’s level of fitness before the break. No one is immune to deconditioning—not the marathon runner, and not the industrial worker.

It makes sense. The less you move, lift and carry—whether on a weight bench or on the shop floor—the more your heart must work. Physical deconditioning means reduced cardiovascular health, muscle mass and flexibility.

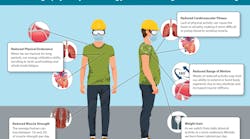

Bianca Sfalcin and Brandon Beltzman, both board-certified ergonomists with VelocityEHS’ Humantech, explain how inactivity causes deconditioning:

Reduced cardiovascular fitness: Lack of physical activity can cause the heart to atrophy, making it more difficult to pump blood to working muscles.

Reduced physical endurance: Our energy utilization shifts, which results in lactic acid buildup and whole-body fatigue.

Reduced muscle strength: The average person can lose between 1% and 3% of muscle strength per day.

Reduced range of motion: Weeks of reduced activity may limit our ability to extend or bend body segments due to less elasticity and increased muscle stiffness.

Weight gain: As we transition from daily physical activity to less, we burn fewer calories.

These losses contribute to performance deficits, quality errors, and an increase in MSDs in jobs where there was already a mismatch between job requirements and human performance capabilities. When the out-of-shape worker is eventually called back to work on an assembly line or in a job that involves material handling, little thought may have gone into the causes and effects of deconditioning. Without engineering controls or processes in place to recondition the worker, productivity issues, quality concerns, and possibly more recordable injuries could land in the organization’s lap.

Lower Back Disorders

Here’s a fact: Whether a worker is fit or not, lifting any heavy object from the ground is considered high risk. Just recently, German researchers conducted a study to examine a new in vivo technique by surgically implanting strain gauges to measure actual spinal loads during a manual lifting task; postural techniques of both squat and stoop lifting were examined.

There are two important findings:

● There is significant spinal load when lifting any object off the ground. This confirms that the magnitude of spinal loading during manual lifting is a primary biomechanical risk factor for low back disorders.

● The maximum spinal forces were basically identical for both techniques, which proves it doesn’t matter how you lift; they’re both bad.

The rate of low back injuries has increased 17% in the last 30 years, and it’s the most disabling condition, according to William Marras, Ph.D., executive director at the Spine Research Institute and Honda Chair professor at The Ohio State University. During his keynote address at the 2019 Applied Ergonomics Conference, he also said, “The prevalence of low back disorders exceeds that of diabetes, COPD and asthma.”

Because the lower back is the most problematic area in the musculoskeletal system and the most easily injured part of the body, he and his team have been hard at work researching ways to remove the risk factors that we are exposed to. We need to be aware of the prevalence, as well as the loads and unintentional forces we put on ourselves, especially since diagnosing and treating back pain is often very difficult.

Back facts:

● Low back injuries account for $15.1 billion in direct costs per year, and at 1.1 the direct costs, an additional $16.6 billion in indirect costs.

● Medical care and hospital services have grown substantially over the past 20 years, and MSDs directly contribute to those costs.

● A precise diagnosis is unknown in 80% to 90% of patients.

● Up to 20% of low back disorders are attributable to push and pull overexertions during manual material handling tasks.

Now more than ever, EHS leaders need to take note of their deconditioned workers and implement controls to reduce MSD risk and lower back disorders.

Making the Workplace Work Better

Sfalcin provides guidance to workers and leadership on how to reintegrate into standard work without impacting manufacturing production and product quality.

Workers should:

Review workstation inventory. Ensure all tools, equipment and supplies are in the correct location and that all equipment is in proper working condition.

Reduce non-value-added activity. Review the on-floor operations and identify ways to eliminate movement waste. This may involve making changes to the workstation layout, organizing the tools and equipment, or determining the most efficient way to complete the task. Especially as everyone practices physical distancing—6 feet apart—consider ways to mechanically transport products between workstations. This will reduce worker bending and reaching when retrieving products.

Identify the tasks that require the highest forceful exertion and the most awkward postures. Analyze the jobs to pinpoint where the highest forces and awkward postures are, determine their true root cause(s), and then brainstorm engineering solutions to eliminate or reduce exposure to them. Implement the improvements that are feasible for the time being.

Implement engineering controls to reduce employee exposure to MSD risk factors. If production is slow, it may be the perfect time to make physical changes to the workstation layout, equipment, or process. Focus on high-impact, low-cost engineering solutions that are quick to implement.

Add additional error-proofing stations. Consider adding temporary checkpoint stations to ensure that all work is getting done correctly. This not only helps ensure that product quality is on point, but it also helps to eliminate rework and waste.

Limit job rotation. If job rotation is not done correctly, it has the potential to increase the workplace injury rate by increasing the number of employees exposed to high-risk jobs. Therefore, it is not an effective ergonomics solution. In addition, less job rotation will reduce common touchpoints among workers, which may help reduce the spread of germs and help employees feel safer.

Bring in healthcare professionals. A physiotherapist or a message therapist can address employee discomfort as soon as it starts.

Managers should:

Ensure all employees complete general ergonomics awareness training to gain a full understanding of what ergonomics is, why it is important, and what is expected of them. Everyone should know the primary MSD hazards so they can identify and report ergonomics issues at their own workstations.

Train each employee to complete an ergonomics self-assessment. Use a qualitative assessment tool to enable employees to assess each task within their day-to-day jobs.

Instruct each employee to review standard operating procedures (SOP). Each SOP should be up to date and available to review prior to restarting work. This can help workers recall all steps in the process or prepare for the next model production. Ultimately, it can help reduce errors and improve product quality.

Limit overtime hours. Employers should consider having more employees work fewer hours, as opposed to having fewer employees work more hours. This will prevent additional physical stress.

Encourage proactive communication. Ensure employees know that they can (and should) report physical discomfort. Whether it is through weekly surveys or ergonomics self-assessments, early reporting will help prevent issues that would otherwise turn into an MSD.

Encourage employees to take all available breaks throughout the day. Breaks from physical activity allow time for muscle recovery.

Encourage employees to focus on personal fitness and overall well-being during their personal time. Advise them to take daily walks to maintain cardiovascular fitness and try at-home workouts to maintain muscle strength and overall fitness.

The good news is that deconditioning can be reversed. Just because you’re unfit today doesn’t mean you have to be tomorrow.

Rick Barker, CPE, is senior technical ergonomics manager, and Jennifer Sinkwitts is senior manager with VelocityEHS | Humantech, a provider of cloud-based environment, health, safety (EHS) and sustainability solutions.

References

Dreischarf M, Rohlmann A, Graichen F, Bergmann G, Schmidt H. In vivo loads on a vertebral body replacement during different lifting techniques. J Biomech. 2016 Apr 11; 49(6):890-5.

CHART CREDIT LINE (“Deconditioning chart”):

VelocityEHS | Humantech