Finding the Key to Responsible Nanomaterial Development

While research continues to uncover the underpinnings behind the potential impacts of nanomaterials and reduce the extensive uncertainties characterizing these novel materials, the need for effective, multi-stakeholder collaborative consortia to develop novel applications in a responsible manner likely will continue. It will require a multi-dimensional approach in which the potential environmental, health and safety risks – along with ethical, societal and liability risks – are well-understood and managed while technological development continues to advance.

While numerous reports and scientific papers have outlined the challenges to understanding the health and environmental risks of nanomaterials, we want to focus on the specific need for effective multi-stakeholder collaborations and propose solutions to enhancing collaborative consortia.

What exactly do successful multi-stakeholder collaborative consortia look like when it comes to responsible nanomaterial development? And how should they operate? We find that despite this need for interdisciplinary knowledge shared across stakeholder groups, there currently are numerous gaps and disconnects. These are occurring not only among diverse sector areas, but also within research communities, not unlike many other scientific disciplines.

After reviewing some of the key barriers to multi-stakeholder collaborations in the case of responsibly developing nanomaterials, we suggest three broad strategies to effectively bring together diverse stakeholders in a successful collaborative effort, as well as specific recommendations on how diverse actors and stakeholders can become better interconnected in order to maximize the potential benefits while proactively addressing the risks of nanotechnology and engineered nanomaterials.

Furthermore, the combination of uncertain regulation, including a lack of an internationally agreed-upon definition of a "nanomaterial" and related challenges, as well as low public knowledge of nanotechnology, leads to a situation in which industry is standing on uncertain ground in terms of marketplace security for nano-enabled products and applications. Strong collaborative initiatives must be an essential part of the solution to try and reap the expected benefits of this transformative technology, while also proactively addressing the potential concerns in regard to health and safety. Some of the many benefits of multi-stakeholder collaborations include:

• Advancements in knowledge of complex systems given time and resource constraints.

• Improved management of uncertainty to bring products to the market and risk-benefit sharing among collaborators.

• Increased network opportunities among specific nanotechnology sectors and enhanced ability to share information and leverage limited resources.

Industry also can benefit from these collaborations through an improved understanding between product developers and regulators, as well as direct access to fundamental research activities. In fact, the numerous benefits of interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder collaboration widely have been recognized in fields far beyond those focused on nanomaterial development.

While numerous organizations, reports and scientific articles have advocated for strong collaboration between diverse sectors and disciplines, some of the key questions remain: What exactly do successful multi-stakeholder collaborative consortia look like? And how should they operate?

To date, a number of multinational and international organizations have been funded in order to enhance greater cross-disciplinary and sector collaboration, including the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) Working Party on Nanotechnology, diverse European Union (EU) framework programs, communities of research and International Organization for Standardization (ISO) technical committees, among others. Some examples of successful public-private partnerships include Nanotechnology Industries Association and the NanoBusiness Commercialization Association, while the Center for the Environmental Implications of NanoTechnology (http://www.ceint.dtu.edu) and its sister center UC Center for Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology (http://www.cein.ucla.edu/new/) are two examples of more academic-based collaborative consortia.

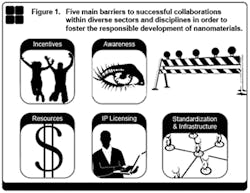

Barriers and Proposed Solutions to Effective Collaboration

Lack of tangible incentives. Without real incentives, particularly for individual professionals, collaborative consortia may struggle to produce fruitful collaborations. For example, academic researchers largely are driven by the need to publish scientific journal articles and participate in activities that have the potential to directly increase their impact factors. Although collaboration with multiple groups could result in increased tangible evidence of productivity (e.g. peer-reviewed articles), participating in multi-stakeholder collaborative consortia may not lead to the production of scientific journal articles or other name-recognition opportunities.

One solution may be to provide more tangible incentives such as additional resources or funding for the larger organizations employing the individual professionals and at the same time providing opportunities for peer-recognition and networking-opportunities for the individual professionals. For instance, universities could include metrics of collaborative work in tenure review for university faculty, or funding agencies could continue to add explicit grant requirements for interdisciplinary collaborations.

Lack of resources. Inadequate funding also has been cited as another significant barrier to multi-stakeholder collaborations. For instance, if collaborative efforts only are on a "volunteer" basis, then it increasingly becomes challenging in terms of the time and resources needed to foster strong collaborative opportunities.

Apart from funding, there also is a need for a large pool of talented scientific professionals who are able to collaborate across sectors and disciplines. We propose additional support from public-private partnerships, whereby graduate students, for example, would have a more direct link to corporate or industrial experiences. This essentially would create a pipeline between academic research and private enterprises, leveraging the strengths of each sector. For example, academic institutes could leverage their shared equipment, while independent research organizations leverage their professional subject-matter experts and startup companies leverage their stock options. This pipeline also could help establish further funding opportunities for multi-stakeholder collaborations.

Lack of supportive intellectual property licensing regulations and practice. The current practice pertaining to intellectual property licensing is a significant barrier, particularly for industry-academia partnerships. While some work has begun to help alleviate these challenges, there still remain significant obstacles in this regard. One solution may be to have a broader discussion among stakeholders in an attempt to define intellectual property. Independent organizations, such as research institutes, could help facilitate this conversation among diverse stakeholder groups.

Lack of proper standardization and infrastructure to support data and information sharing. Multi-stakeholder collaborations focused on promoting the responsible development of nanomaterials may face uphill challenges given the lack of a standard definition of nanomaterials. For example, the ISO Technical Committee 229, formed in 2005, has made good progress but is limited by the number of volunteer experts and lack of knowledge by users of the available, finished standards.

There also is a need for proper infrastructure to support data and information sharing across stakeholder groups. While some organizations have responded to this need by establishing various databases and infrastructure to handle large data sets for nanomaterials (such as the Nanomaterial Registry, RTI International 2013), we propose the continued support of these initiatives in order to facilitate information and data sharing across stakeholder groups.

Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration Needed

In order to most effectively bring together diverse stakeholders in a successful, collaborative consortium focused on promoting the responsible development of nanomaterials, we propose three broad strategies.

1) Continued support for existing collaborative opportunities, such as the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI). The NNI is a research and development initiative funded by the U.S. government to promote the development of nanotechnology in a way that promotes society. Further support of the NNI could help promote multi-stakeholder collaborations, particularly since the infrastructure and outreach already have been established.

2) Development of new, collaborative research centers that would be operated by independent organizations to facilitate knowledge transfer from the R&D phase to application phase. This new collaborative research center would use existing infrastructures, and would serve as a leader to help multiple stakeholders interact and share data, among other activities. Independent organizations such as research institutes ideally would be positioned to host such a new collaborative center, since they typically have in-house experts in critical fields of material and technology development, eco-toxicology, risk management and economic expertise to help translate technological advances to viable applications. Third parties such as independent research institutes also typically have close ties to diverse stakeholder groups and can serve as neutral facilitators of confidential information or stakeholder needs.

3) Establishment of collaborative research centers that would house multi-stakeholder interactions in established infrastructure. This would be similar to the previously described strategy, although this option would provide collaborative infrastructure, similar to research "campuses" where multiple stakeholder groups would collaborate in strategically designed buildings and laboratories to house these interactions. Independent organizations such as research institutes also would be ideal candidates to house these new collaborative research centers, as they strategically are positioned to facilitate the interactions with multiple stakeholder groups.

In addition to these three proposed broad strategies, we also provide specific recommendations for industry, academic institutions and government agencies in order to effectively promote the responsible development of nanotechnology (see box below).

Although multi-stakeholder collaborations are essential to ensuring the sustainable development of nanotechnology, nanomaterials and products containing them, there still remain numerous barriers among disciplines and sectors to fully realize these collaborative opportunities. Some of the main barriers to effective collaborations include the lack of:

• Tangible incentives for both individual professionals and their organizations;

• Dedicated resources in terms of funding and a pool of talented scientific professionals to help movement between academic research and private enterprises; • Universal awareness of collaborative opportunities across stakeholder groups;

• Supportive intellectual property licensing regulations and practice; and

• Proper standardization and infrastructure to support data and information sharing.

For each of these aforementioned barriers, we propose analogous solutions to overcoming these.

We propose three strategies to effectively bring together diverse stakeholders in a successful collaborative consortium, including the continued funding of existing collaborative initiatives such as the NNI; the development of new, collaborative research centers operated by independent organizations; and the establishment of collaborative research centers that would house multi-stakeholder interactions in established infrastructure. Third parties such as independent research institutes can help facilitate better multi-stakeholder collaborations by balancing the needs of industry and regulatory bodies in a neutral setting. Third-party entities also can help facilitate the handling of confidential, proprietary information from industry in an anonymous way, which may be useful to better understand the safety of nanomaterials and products containing them. Three primary stakeholder groups (industry, academia, government) can help facilitate multi-stakeholder collaborations to promote the responsible development of nanotechnology and nanomaterials.

By Khara D. Grieger (RTI International ), Christie Sayes (RTI International), Christine Ogilvie Hendren (Center for the Environmental Implications of NanoTechnology ), Ginger Rothrock (RTI International), Carol Mansfield (RTI International), R.K.M. Jayanty (1RTI International) and David Ensor (RTI International). RTI International is located in Research Triangle Park, N.C. The Center for the Environmental Implications of NanoTechnology is located at Duke University in Durham, N.C. Corresponding author Khara Grieger can be reached at [email protected].