Do we really want to get rid of the word “accident?” While there is a definition of accident on its website, the National Safety Council is trying to get rid of the word from its materials “because workplace incidents are preventable,” according to Kathy Lane of the National Safety Council. The problem is whether any other term would carry the same impact. And would insurers accept any other term as the basis for any form of reimbursement? “Accident” gets attention!

We do need to get rid of the perception that if you are working in hazardous conditions that sometimes you are going to experience an accident or injury, and there’s nothing you can do to avoid it.

What safeguards are there for those who work in dangerous occupations? The critical ones include extensive training, physical and mental fitness, appropriate personal protective equipment, constant risk awareness and the ability to respond to unplanned circumstances.

We must consider that no accident is accepted as the cost of doing business, no matter how hazardous the job. To make strides toward this goal, there must be ongoing efforts expended to improve safety awareness, such as:

- Work to eliminate all injuries, not just the severe ones.

- Incorporate prevention by design, where safeguards are engineered into equipment and systems, rather than installed as an afterthought.

- Provide meaningful training.

- Stress accountability for safety across the entire chain of command as a condition of employment. The ultimate responsibility for safety must rest with each individual.

- Raise awareness of hazards and the associated risks by constantly sharing information.

The risk posed by a hazard incorporates a number of factors, such as probability of accident occurrence if appropriate action is not taken; severity of outcome if remedial action is not taken; and the frequency in which people are exposed to the hazard.

Each of the three elements can be evaluated on a numerical scale from minimal (1) to catastrophic (5). It’s a good idea to ask a cross-section of the workforce to participate in such an evaluation in order to identify and classify all of the hazards (both obvious and hidden) that may be present. Adding up the three numbers for each hazard prioritizes them. If you have a safety management system, this is a way to identify your significant safety hazards.

If you find it difficult to decide which numerical hazard rating number categorizes a hazard as significant, you might want to use the risk score formula developed by F.A. Manuele, which can assist in making a more objective decision by classifying calculated risk numbers into four decision-making categories.

Workplace injuries are tabulated annually by the Bureau of Labor Statistics into 12 major categories: overexertion; struck by; struck against; falls to lower level; falls on same level; slips, trips, loss of balance, no fall; caught in; exposure to harmful substances; transportation; repetitive motion; assault/violent acts; and, fire/explosion.

While the number of incidents in each category varies slightly from year to year, typically, 70 percent or more of accidents can be grouped into just four condensed categories – overexertion; slips/trips/falls; struck by; and struck against. Looking at the number of in-house incidents in these four areas provides a starting point to concentrate abatement efforts for the maximum impact.

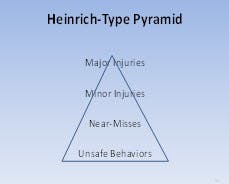

After analyzing thousands of Travelers Insurance Co. accident reports, H.W. Heinrich in 1931 estimated that, for every 300 unsafe acts, you could expect 29 minor incidents and 1 major incident. HeA later study, conducted in 1969 by Frank E. Bird, Jr., analyzing over 1.7 million Insurance Company of North America accident reports, concluded that for every 600 near misses you could expect 30 incidents of property damage, 10 minor injuries and 1 serious/major injury. He emphasized the importance of directing efforts at reducing the occurrence of not only serious but of less serious events, which could ultimately reduce the number of major injuries, especially low probability events that often defy explanation.

While there has been much discussion of late on the validity of Heinrich’s conclusions, each of us experiences far more near-misses and minor injuries than major injuries over our lifetime, either on or off-the-job, i.e., our own personal Heinrich-type pyramid.

System Error

One way to document the status of a safety program using trailing indicators is to plot three monthly totals: all incidents (near-misses, minor incidents, recordables and lost workday incidents); recordables; and lost workday incidents.

Doing so will probably show a lot of variability at first, but once you have sufficient data to plot 3, 6, 9 or 12-month totals you will see that the plots track each other, confirming Bird’s suggestion that attention directed toward low impact events may well reduce the potential for larger impact events.

The term “human error” may no longer be politically correct because it can imply that accidents are almost entirely the fault of the person or persons involved.

Another approach to consider is how many incidents are the result of “system error.” In other words, there is something in the way things are done (the culture) that seems to tolerate or even encourage unsafe actions. For example:

- Supervisors failing to enforce safety rules

- Tolerating short cuts

- Tacit approval that ignoring standard procedures is acceptable

- The feeling that “I’ve done it for so long, and never gotten hurt” (low probability error)

- Equipment designs that don’t take safety into account

- Ineffective safety procedures

- Lack of or ineffective training (“check the box” training)

- Failure to maintain equipment

- Failure to fix identified hazards

- Skirting safety procedures in the interest of productivity

- Allowing warning signs or labels to deteriorate to the point that they are no longer seen

Vince Lombardi once said, “Gentlemen, we will chase perfection. And we will chase it relentlessly, knowing all the while we can never attain it. But along the way we shall catch excellence.” If ever there were a statement to sum up the task of safety people, this is it.

In order to make progress toward an accident-free working environment, we need to move away from placing blame when things go wrong (using human error as a default root cause of incidents) and work to make the work environment as risk-free as humanly/economically possible by:

- Conducting frequent safety inspections and correcting all findings, no matter how minor, as soon as possible

- Never being content with a safety record, no matter how good it may be

- Requiring that safe work procedures be followed at all times

- Conducting Job Safety Analyses to identify the hazards of each operation

- Using Job Safety Analyses as the basis for effective on-the-job safety training

- Worker involvement in the safety process

- Active supervisor oversight and mentoring

- Not tolerating short cuts

- Effective/ongoing safety training that ensures that the training sticks

- Encouraging employees to watch out for each other

- Active involvement of all levels of management in the safety process

- Effective accident investigations

- Eliminate “told employee to be more careful” as the default conclusion of accident investigations

Even with hazards reduced to the lowest possible level, people still make mistakes that can lead to accidents.

The 12 main causes of accidents (see above) are no surprise. However, a thorough accident investigation is needed to identify the reasons for the causes. Reasons are the actions, conditions, or lack of actions that, if addressed, can prevent accidents from happening. There may be some human elements that need to be addressed but only if people are told why certain actions are unsafe and are given the tools and knowledge to correct them. Some possible reasons include:

- Lack of knowledge about what hazards exist

- Failure to recognize risk or anticipate the unexpected

- Rushing

- Inattention

- Complacency (“Done it so often and never gotten hurt”)

- Didn’t think before acting

- Feeling of invincibility (“Won’t happen to me”)

- Low probability error (the “one in a million” event)

- Bad judgment/Bad choice

- Wrong place at the wrong time

- Lack of supervisory enforcement of safety rules and work procedures

- Poor equipment design/No safety devices

- Ignoring hazards or safety warnings

- Not following safe work procedures

- Improper/faulty tools/equipment

- Trying to do too many things at the same time

- Taking short cuts

- Ineffective safety procedures

- Frustration

- Fatigue

- Failure to use appropriate caution

- Lack of/inadequate training

- Putting production or schedules ahead of safety

- Bypassing interlocks or machine guards

Sharing information about these activators on an ongoing basis can’t help but raise awareness for employees, who can then file them away as common sense things that can be recognized as an effective way to reduce and eliminate unsafe actions.

You can’t do anything about what has already happened (trailing indicators). You can, however, use accident data to alert people to past or recurring hazards. You can’t just tell people to be safe. You must tell them what it takes to be safe.

What is takes can be summed up in one word: awareness. People must be aware of what can make them unsafe.