SLC 2016: LOTO vs Alternative Protective Measures

Safety doesn't have to come at the expense of productivity.

That was the common refrain ringing through every session the Smart Manufacturing track at the 2016 Safety Leadership Conference. Every discussion of IoT, the Connected Enterprise, safety technology and robots sang that same song, all of them offering new tools and new strategies to keep workers safe while keeping plants running smooth.

Until we got to lockout/tagout.

Of all the safety mechanisms in the plant, this one is the only real, undeniable productivity blocker, literally shutting down production at its power source to keep workers safe.

But it's for a good reason.

In his presentation on advanced lockout/tagout strategies, Tim Bohmann – Global Business Development Manager at ESC Services – gave us some dire statistics.

"Twenty-on amputations occur every day in the U.S. workplace," he said. "That's 7,990 amputations per year."

This, he said, is exactly what LOTO was designed to prevent.

"Lockout/tagout is meant to prevent tragedy," he explained. Which is why LOTO failures have consistently been in the top 10 most cited OSHA violations list every year since the standards have been in place: Lives and limbs are on the line.

But then Bohmann brought up another curious statistic.

Despite all of these regulations, all of the fines they carry, and all of the work EHS professionals have done to prevent tragedies in the workplace, "over the last 20 years, there has only been a 1.5 decrease in deaths per year," Bohmann said.

This slow progress, he suggested, means, "There is still much more room for improvement."

It also suggests, in spite of all the efforts in place to prevent it, there is something still compelling workers to put themselves in danger.

Rockwell Automation's George Schuster has an idea why.

An Alternative Approach

"Why do workers bypass lockout/tagout?" Schuster asked the crowd in his SLC 2016 presentation, "Alternative Protective Measures."

"It's not because they have too many fingers," he said. "People are trying to optimize their work; they are trying to do their jobs."

Basically, he said, these workers still feel that standard LOTO practices are standing in their way.

But maybe not anymore.

Recently, he explained, OSHA updated its LOTO regulations with a new note laying the groundwork for Alternative Protective Measures (APMs) for exactly this kind of scenario:

"In a nutshell," Schuster said, "Alternative Protective Measures are a substitute or are used sometimes in lieu of lockout/tagout under very specific circumstances of very specific tasks."

The key to that explanation, of course, is in the last "specific" bit.

"LOTO is for any task in any area," Schuster said. "APMs are for very specific tasks in very specific areas."

More to the point, they apply only to tasks that are "routine, repetitive, and integral to production." This includes jobs like cleaning jams or adjusting products in machines—tasks routinely needed to keep the process running and that don't put the operator in any added danger.

But meeting that last part takes some work.

Engineer It Out

The point of APMs isn't just to unlock machines and let workers play unguarded inside. It's a system that, by definition, must be exactly as safe as LOTO even without powering down.

"We can't allow any increased risk," Schuster explained. "We need equivalent protection. So we have to be smart; we have to engineer it."

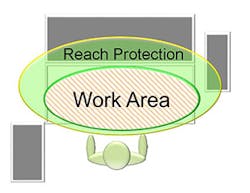

And that means designing a system filled with light curtains, guards, indicators, and, yes locks—whatever the system needs to ensure that operators only have access to the parts of the machine needed to perform routine, repetitive maintenance that is integral to production.

To design all of that, safety engineers need to start with a familiar tool: the risk assessment."

"Risk assessment is the key," Schuster said. "It forms the basis of any complacent system or APM and is key to establishing the circuitry performance in lieu of lockout/tagout."

From there the process follows the usual safety process: training, procedures, policies, documentation, and, of course, regular audits.

The Bottom Line

The goal of APMs goes back to that original refrain: it brings productivity back to safety.

And this one hits that note strong.

"The impact of reduced lockout/tagout is significantly increased production," Schuster said. "My calculations generally come up with millions or tens of millions of dollars in savings per year."

To prove that point, he left the crowd with the following case study from ESC Services.

As detailed below, in the original procedure, every time operators had to change a die, clear a part, or make a minor adjustment on this press, they would initiate a six minute lockout process that cost the company as much as $315 every time.

The APM system brought that whole process down to under a minute: